Advice

Loving Justice Conference Plenary Notes

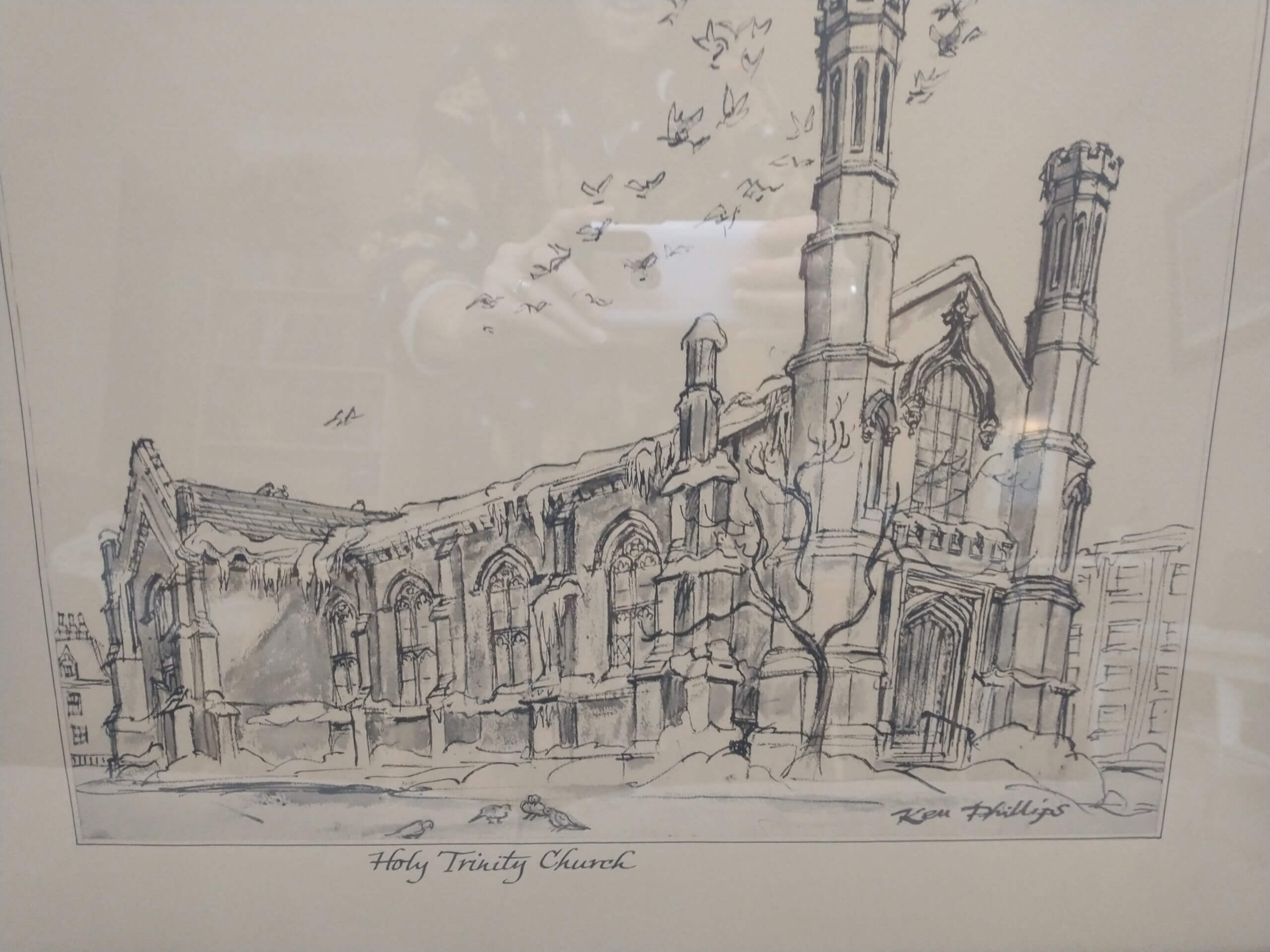

Church of the Holy Trinity, December 7-9, 2000, Toronto, Ontario

For individual use. Reuse, publication or printing requires author’s permission

- Keynote Address Mary Hunt

- Response to Questions Mary Hunt

- Response by Richard Holloway

Mary Hunt Keynote Address

“Ready or Not, Queer We Come”

This morning I would like to turn our attention away from the immediate struggle on sexual issues as such and to the larger context in which we find ourselves as it relates to our concern for sexual justice. I will do so in three moments: first, sketching the context, second, naming several issues that arise as we seek justice, and third, exploring some of the dimensions of holiness that shape our agenda as we challenge the churches of which we are a part. I do so from a white, US, Roman Catholic, lesbian feminist theological perspective with all of the limits and possibilities entailed in each of those aspects of my position. But I do so as part of a larger Christian community that has struggled mightily, and in many cases disgracefully, over sexual issues that are increasingly accepted in the society as a whole. So, my frank and critical comments are meant to push the process along lest we end up as the tail wagging the dog, as people of faith who are wholly irrelevant to the communities in which we live. Let me turn then to those communities in an effort to situate our efforts to bring about queer justice and queer holiness.

Context

I want to look broadly at what I take to be our cultural setting shaped largely by five interlocking factors which I will sketch so as to assemble us this morning on something like the same analytic page. You may wish to add other factors, but I think these five provide a rough outline of where we begin as we seek queer justice. They are:

1. Globalization and technology

2. Economic inequality

3. HIV/AIDS

4. Violence

5. Religious Pluralism

Let me look at each in turn:

1. Globalization and Technology Globalization is a word used frequently to mean the degree to which more and more decisions are being made by fewer and fewer people. It is the consolidation of business, industry, government, culture, and yes even religion so as to streamline choices to very few made by very few. Some call it the “coca cola-ization” of the world. I like to think of it in terms of the pernicious ubiquity of McDonald’s where it is mandated from the McDonald’s University in Chicago that the lettuce goes beneath the tomato and not vice versa. This means that a short order cook who used to be able to prepare your lunch as you wanted it is now forced to work for minimum wage at fast food places all over the world and prepare the burger as specified in Chicago. When she balks at this approach there is someone ready to take her job. In practice, globalization has all of the positive aspects with which we are so familiar as we build our movements: air travel, Internet access, and fax. But in fact it literally cashes out to more decisions being made for increasingly larger sectors of the world by increasingly fewer people. In a globalized economy some companies like Nike have budgets that are larger than the budgets of some developing countries so decisions made in those company boardrooms carry more weight than those taken in some legislative arenas. Transnational corporations and not governments have the greatest power. A recent map in the New York Times paired countries’ Gross Domestic Product with transnational companies’ market value: Spain at $594 billion is the size of Microsoft; IBM at $201 billion is now the size of Colombia; General Electric at $456 billion now equals Thailand. You do the math and then let’s talk about queer justice. None of this would be possible without the explosion of technology that has literally reconfigured the world as we know it. We have experienced a geometric increase in the speed and scope of communication for those who are on-line, and an equal and opposite disempowerment of those who are not. Air travel has increased far beyond the ability of medicine to keep up with the jet speed spread of some forms of disease. I can not decide which toy I could live without– my computer, fax, Internet access, cell phone, all the chip driven things that have made life radically different from even ten years ago. But it remains still a matter of luxury on a worldwide scale. Queen justice begins here, not in the bedroom or the bushes.

2. Economic Inequality This leads to the second contextual dimension, namely, economic disparity. While many of us have our cell phones in our pockets, it is estimated that twothirds of the world’s people have never made a phone call. Numbers numb, but 80% of the word’s population have an income of less than $700 a year. Think about what you make in a month. More to the point, even with the stock markets reeling wildly, we can now speak meaningfully of those who are invested and those who are not when we think about future wealth. In the U.S., the salaries of those at the upper end of the pay scale are now in some cases 40 to 70 times those of people at the bottom with no end to the disparity in sight. The U.S. is unquestionably the engine behind economic inequality, living with unnaturally low gas prices and spending less of our income on food than any other country in the world. Queer justice continues here with economic decisions, in my judgement, far more critical than who does what with whom in bed. Queer justice can be distracted by the microscopic rather than the macro issues.

3. HIV/AIDS Into this globalized inequality comes HIV/AIDS. According to the United Nations report issued to coincide with this annual celebration of the pandemic, AIDS has already taken 21 million lives. Worldwide, the number of people now infected is fifty percent more than had been predicted a decade ago. Complacency in the West is cited as a major public health obstacle. Queer justice is needed here. Indeed HIV/AIDS is eliminating those who are considered expendable– poor people of color, especially women and children, gay men, IV drug users, all those who are best tagged “throw away people.” It is morally unspeakable, but taking a page from ACT-UP, our silence will kill them. In 1994, the late Jonathan M. Mann, a medical doctor and public health expert who led the World Health Organization’s early AIDS prevention efforts, presented Harvard Divinity School’s Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality. He issued a wake up call to the religious community, not to the scientific community, but to those of us who looked optimistically to science to solve this terrible global problem. “A new AIDS strategy must have two major components. The first part must address AIDSspecific issues like ensuring the safety of the blood supply, educating about safer sex, distributing condoms, or preventing HIV spread among injecting drug users. This is the usual domain of public health work. The second part of a new strategy must focus on the underlying determinants of vulnerability to HIV. Beyond the many specific AIDS issues and problems lies a short list of deeper societal issues.

A useful way of summarizing the “root causes”– including societal taboos, unequal importance given to certain groups of people (women, gay men, developing countries), and inequitable distribution of resources– is to recognize the common denominator of a lack of respect for human rights and dignity.” i I am sad to report that Dr. Mann’s words were prophetic then, but tragically, had he not been killed in the Swiss Air crash a few years ago, he could have written them yesterday as they contain the heart of the matter. While science looks for a vaccine that is the only long-term solution to this problem, and perfects the drugs that work to improve the quality of life and the life expectancy of those who are infected, the weight of Dr. Mann’s words on the “root causes” of HIV/AIDS falls on us, the religious people who are charged with the moral and religious well being of our people. Note that he did not say that churches should deal with sex as such, but with the root causes of injustice. There is a difference.

Unhappily, we have accomplished precious little in changing the factors he cited as the reason why HIV/AIDS cannot be solved by science alone. The racism that permits us to think of Africa as an exotic other planet continues unabated with some African countries such as Botswana, Namibia, Swaziland and Zimbabwe now saddled with infection rates approaching 20 % of their citizens between the ages of 15 and 49. This same racism lifts rates of infections among people of color in my country well beyond their percentage in the population. The sexism that keeps women vulnerable to unwanted and unsafe sexual advances and has made HIV/AIDS an equal opportunity killer shows no signs of let up. The economic privilege endures that permits some of us the luxury of ignorance to think that just because some people are living well with the disease we can get back to our holiday shopping. Grossly unequal access to health care worldwide dictates that some people who receive social services discover that they are better off HIV positive because they can get more help than if they are negative. Beyond unspeakable, this morally hideous situation spawns the heterosexism that leads some young gay men to engage in unsafe sex. They reason it is better to be part of the HIV-positive community than to be simply a young queer kid alone because at least positive there is some community. Moreover, the ageism that lets us ignore our seniors’ sexual activities until it is too late and they are infected persists without a peep. We have work to do. These are precisely the social issues to which Dr. Mann made reference. But with 15,000 people becoming infected every day around the world, that means 5.3 million more infected by this time next year, including 6000,000 children under age 15. Let us speak of queer justice using HIV/AIDS as the test case.

4. Violence Such talk of HIV/AIDS leads to consideration of another factor that shapes the contemporary context, namely, an increase of racism and violence in many forms, including environmental damage. Here I am deeply influenced by living in one of the most violent countries in the world. I want to describe these problems in broader terms than simply U.S. culture. Racism takes such a variety of forms, all of them violent, with poverty, joblessness and lack of access to education continuing from one generation to the next. Virulent hate crimes and continued anti-Semitism plague many countries. Globalization means an increase of concentration of wealth in the hands of a few, a form of violence. Weapons from street guns to weapons of mass destruction continue to proliferate as a major business. Controversy over land mines left over from previous wars continues with my government refusing to lead the way toward disarmament. Global warming threatens all of us, a complicated but preventable form of violence. You may wonder what all this has to do with queer justice. I suggest that unless we are struggling realistically within this context we run the risk of fiddling while Rome burns, focused on a small piece of a huge agenda such that we are distracted from the whole.

5. Religious Pluralism One more factor in all this least in the U.S., presumably in Canada, and I think around the world, is the increased pluralism of religions. Diana Eck, Professor of Comparative Religion and Indian Studies and Director of the Pluralism Project at Harvard University describes one aspect of the situation when she show how the U.S. religio-cultural landscape has changed from a three-religion culture (Protestant, Catholic and Jewish) to one in which there are “more Muslims than Episcopalians, more Muslims than Presbyterians, perhaps soon more Muslims than Jews.”ii She writes: “America today is part of the Islamic, the Hindu, the Confucian world. It is precisely the interpenetration of ancient civilizations and cultures that is the hallmark of the late twentieth century.”iii While Canada and the U.S. are quite different in some regards, I think you will agree that the globalized migration of peoples for work and survival makes this new religious pattern common. In Latin America, for example, one sees the end of Catholic hegemony in sight and the emergence of Protestant Evangelical, Jewish, and yes, even some Buddhist and Hindu influences in some communities, especially in Brazil. New Age and Goddess groups abound in many cultures. It used to be conventional wisdom that to know one religion was to know all religions. Now, it seems, to know one religion, as Professor Eck observes, is to know no religion at all. This is increasingly true in Canada. I bring this to our attention because at a conference like this with a well-focused agenda on change in a particular faith community we can lose the big picture in which our religious community is set. This is a new context and invites interfaith, ecumenical work to become the norm when working on queer justice and queer holiness. When taken as a whole, these five elements add up to a less than welcoming world for the vast majority of its people, especially women, people of color, those who are poor, ill, very young and very old. That does not leave many of us! Imagine being a young transgender person in Zimbabwe or an elderly lesbian in India. Think of yourself as a factory worker who thinks he’s gay in inner city Detroit or rural Saskatchewan. Put yourself in the shoes of a First Nation’s woman who is bisexual and think about safety, health and opportunities. This is where queer people live. My conclusion is that in an unjust context Christians who are committed to the radical equality of the Gospel must be about wholesale justiceseeking, not just tinkering with a few issues like who has sex with whom but transforming the context in structural ways.

Justice Issues In such a context I want to raise three issues for our consideration as we go about this challenging task within the Christian churches: 1. We’ve only just begun 2. Queer justice focuses on sex but is much more encompassing 3. Backlash is a sign on progress but it hurts nonetheless

1. We’ve only just begun First, it seems to me, and here I will overstate the case but I think you will understand what I mean, that much of the theo-ethical work to show that gay and lesbian people are healthy, good, natural and holy has been done. Here I mean the work of John McNeill and Carter Heyward, Virginia Ramey Mollenkott and John Boswell, to name just a few of the pioneers. This is not to say that such work has trickled down where it needs to be, in which case we would be dealing with economic issues and anti-racism this weekend and not sexual justice though they are connected. But there is scholarly work in abundance with plenty more in the pipeline. This issue now is theo-political not theological, that is, the issue is how the ecclesiastical powers that be will handle the new revelation that these scholars bring to light, revelation based in real human experience. There is an overwhelming body of work in virtually every field– from church history to systematic theology, from ethics to world religions, from sociology of religion to the biological/physical sciences– to prove beyond doubt that homosexuality is healthy, good, natural and holy.

Of course more work is needed, for example on bisexuality. We say glbt quite easily, but we have precious little work on bisexual experience and what it means for the rest of us. On the one hand, it reinforces the binary categories we seek to overturn, but on the other hand it creates space for those whose experience it describes. Justice entails the human right to describe one’s experience and have it taken seriously. With Debra Kolodny’s anthology Blessed Bi Spirit we have a start, but much remains to be said and done to bring about justice for our bi friends. Where this gets tricky, however, is when we take seriously the experience of transgender people. Sarah Ivy Gibb, a student at HDS wrote an excellent paper on “Pastoral Care with Transgender People” which I find very useful on this issue. The fact is that we use the term “trans” without knowing much. We need to distinguish, as Sarah Gibb does in her work that follows, among several categories: a. Crossdressers/transvestities (mostly heterosexual men acting in private) b. Transsexuals (people who feel they are different gender than what was assigned to them based on biological criteria) c. Third gender or transgender (people who name their gender identity beyond male/female categories) d. Intersexual people (people whose biological sex at birth transcends the categories of male and female, sometimes known as hermaphrodites)iv

There is much to discuss here, indeed much to understand before we too blithely use the word “queer” without realizing the implications. For example, transsexual Martine Rothblatt in The Apartheid of Sex uses colors to describe sexuality as in today I am green, tomorrow yellow. There is a group in Chicago that calls self bi-gendered (male by day, female by night). Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, one of our trusted foresisters in this work, has a book coming out this spring entitled Omnigender in which she draws out theological and moral implications of opening ourselves to the vast variety of human experiences and reconfiguring our categories accordingly. The point is how can we speak of queer anything without investigating, exploring, and analyzing the specificity of the experiences involved? I submit that what the trans movement does is to undermine the categories we use to speak of gender. Is the essentializing of male/female with its attendant sexual orientation/identity categories of lesbian/gay (same sex love) simply outmoded? Must we speak now of a glbt movement, or a queer movement as something quite different from the old gl even glb movement? I tend to think so because the ground is shifting under our feet. Not to do so is to calcify as a movement in categories no longer relevant to the experiences of young people. For example, a male to constructed female transgender person who has a woman lover is arguably a lesbian. But when trans writer/activist Kate Bornstein says she wants to be not a man, not a woman but a girl I think we’ve got some work to do.

My conclusion is a practical one. Even though many religious folks can’t tell the players without a scorecard, we need to be asking new questions. I suggest that the days of glb life are behind us and transgender questions herald a whole new queer movement that those of us who have been part of the old need to retool for as well. Now the questions of nature/nurture, sexual orientation chosen or given, sexuality as static or dynamic intensify in complexity when such essentialist notions as male and female fly out the window. I concede that none of this is easy, indeed none of it is neat and tidy. In fact, I have had to rethink a good deal about myself as a woman I think, as a lesbian I hope, which is to say that we all begin anew, those who have supported and those who have opposed what has gone before. The moral, if there is one, is that if you are not on board with the glb issues you have work to do. It is only going to get more complicated. Even if you are on board, you’ve got more work to do because it is only going to get more and more complicated. When a male student walked into my office and claimed that he really thought he was a woman but didn’t want to do anything surgical about it I was reminded of that biblical passage we know so well: “Male and female God created them…” From a queer hermeneutical perspective it surely takes on new meaning. My point is that we give it the meaning, and our input is not trivial. We’ve only just begun.

2. Queer justice focuses on sex but is much more encompassing My second claim is the notion that queer justice focuses on issues of sexuality, but in fact is really about the range of justice-seeking actions that emerge from the fundamentally unjust context I have sketched. I think I made this clear in my context setting, but let me give an example to ground what I mean. In Washington D.C., we had a terrible death when a male to constructed female transsexual was in a car accident. When the emergency medical personnel arrived, they delayed treatment while they made cutting remarks that this was really a man not a woman. She died. Her family sued and won. That city, that can’t afford to plow its own snow, ended up paying millions of dollars. Everyone learned a great deal as her mother, an African American woman of modest means, became a primary spokesperson for the trans community. For me this case embodies the “tough spun web” (to use songwriter Carolyn McDade’s phrase) of justice needed: racial and economic justice since the color of her skin and the location of the accident surely affected treatment; sexual and gender justice so that our genitals do not dictate life or death. May she rest in peace. Queer justice begins with sexuality but encompasses the whole person.

3. Backlash is a sign on progress but it hurts nonetheless Following Lambeth you need no new examples of backlash. But it may comfort and inspire you to know that backlash is omnipresent at the moment. I do not want to be conceived of as a theological Pollyanna, but I believe that backlash is a sign that we are making remarkable progress. Let me share my analysis of a recent Roman Catholic pronouncement to make this case. Just this fall a new document against “de facto unions” was released by the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for the Family.v It claimed that gay/lesbian unions are “a deplorable distortion of what should be a communion of love and life between a man and a woman in a reciprocal gift open to life.” The document continues, “Furthermore, the attempts to legalize the adoption of children by homosexual couples adds an element of great danger to all the previous ones. The bond between two men or two women cannot constitute a real family and much less can the right be attributed to that union to adopt children without a family. To recall the social transcendence of the truth about conjugal love and consequently the grave error of recognizing or even making homosexual relations equivalent to marriage does not presume to discriminate against those persons in any way. It is the common good of society which requires the laws to recognize, favor and protect the marital union as the basis of the family which would be damaged in this way.” (par. 41-46 ) What is remarkable is that glbt unions have come so far so fast as to be included with divorce and heterosexual co-habitation in the eyes of the Roman Catholic Church. Of course I reject out of hand such codified discrimination. But I want to look closely at some of the assumptions because they reflect some of the thinking of other denominations and traditions, even though those groups are not as unabashed about publishing such nonsense. Also, this is important because it is so clearly at odds with what so many scholars/activists, parents and neighbors experience. This document was not written twenty years ago, but released just this fall (dated July 26,2000, the Feast of Saints Joaquim and Ann, alleged parents of Mary) so potentially, though not apparently, its writers could be aware of modern/postmodern queer theory and theology. Among the operative assumptions is the notion that according to natural law, sex and gender are given and unchanging. This conflicts with everything we now know about gender elasticity, especially the variety we find within gender categories. Take Boy George and Martina Navartolova. Many women have more in common with Boy George and many men with Martina than with those of their respective gender assignments. Thus, the anthropology on which the document is based is seriously flawed since it claims that marriage is unique because men and women are unique: “marriage… is a union between a man and a woman, precisely as such, and in the totality of their male and female essence.” (par. 38) Such language no longer makes sense in English. It no longer corresponds with how we see world. Another problem is that churches like Roman Catholicism take the power/authority to pronounce such notions in the name of all adherents when in fact they represent the views of a few. They are able to say such nonsense without evidence, in the face of a preponderance of evidence to the contrary. Many studies glbt families show remarkable stability with “divorce” rates not as high as those of heterosexual. So far no lasting impact has been found on their children other than a residue of love. Many Catholics understand this. Likewise, in such a situation we have no sense of who serves on Pontifical Council for the Family. There is no minority report, no glbt or women’s caucus. In short, there is no accountability. Another problem with this work is that the language has an impact in the real world. Governments use such rhetoric as if it were true to base laws against granting same-sex rights. It inflames rather than informs general discussion. It is intrumentalized at the international level such as happened when the Catholic Church spoke out against women’s well being at the United Nations meetings in Cairo and Beijing. In addition, such pronouncements are based on the view that anything outside the heterosexual monogamous sexual norm is “disordered” and therefore sinful despite mountains of evidence to the contrary. This comes from the same source that negates masturbation, the use of condoms and other forms of birth control, that outlaws abortion. What are the odds they got this one right?

Some may conclude that Catholicism is an extreme case. I agree. But I am equally convinced that it represents the paradigmatic view held by other religious groups that are just not as out front in articulating their assumptions. For example, the struggle within Anglican churches to ordain or not ordain glbt people is couched in lovelier language but has the same end result. The Presbyterians’ mighty battle over open and affirming, practicing homosexuals is based in similar arguments buttressed by scriptural claims. Likewise, the Methodists’ wrangling over their clergy presiding at same-sex unions comes from the same point of view. We can thank Catholics for clarity if not charity. Let’s look more closely at the problem.

1. tradition- Rather than fresh theological thinking on this question, most conservative approaches are usually based on their own versions of tradition. That is, church documents quote other documents not contemporary sources. Churches rely almost entirely on their history and polity rather than on any fresh hearing of what successive generations bring as wisdom. In addition to being intellectually embarrassing, what happens is that such churches and many people, especially young people are ships passing in the night. There is a nearly complete disconnect between contemporary glbt experience and this kind of pronouncement precisely at a time when we need the “renewable moral energy of religion” (Daniel C. Maguire) to guide us in developing new norms for safe, community-building, mutual human behavior, including sexuality.

2. modes of interpretation–Another problematic aspect is not so much the interpretation as such, but the modes of interpretation that are employed to deal with sacred texts to bolster such positions. Texts like 1 Tim. 3:15, “the church of the living God, the pillar and bulwark of truth,” are taken literally. This is what happens to texts having to do with homosexuality. Scripture requires a much more involved discussion, but the short version is to note the kind of literalism that surrounds such notions so as to avoid the protracted battles over texts that are really struggles over modes of interpretation.

3. social construction of community– What is perhaps most problematic is the social construction of and sense of entitlement around who constitutes the audience for such documents, indeed who is church. By what authority are such pronouncements made and in whose name? I note that in most cases what is at stake is not so much what sexual orientation/identity or integrity is allowed, but who gets to decide. I can imagine a more enlightened view of sexuality coming before this kind of power is shared, underlining that sex is not the only, or perhaps the most important matter in such an unjust setting. It represents much more injustice in the way it is discussed.

4. what the market will bear– Religions participate in the market place. Churches are businesses that have to worry about money, personnel and customers like any other business. Indeed they are not infinitely resistant to change if they want to survive. That is why the document I quoted and the many struggles we are familiar with in our various religious traditions are so interesting. As the society becomes more and more welcoming of human diversity, churches have no choice but change and grow or resist and shrink. What gives me such hope in the midst of this backlash is that we are obviously having an impact. In the short run, backlash is hard to deal with. But in the long view, now 30 years later we can claim to have made enormous changes in a relatively short time. What we are doing is working with more on tap. For example, Mel White and Soulforce, the nonviolent civil disobedience group plans to go to the Vatican in January 2001 to lodge their protest. After protesting the U.S. Catholic bishops in November, to be greeted with this document on “de facto unions” was the last straw. After carefully explaining to bishops that such language helps to create an environment wherein hate crimes occur, people lose custody of their own children, there is a high suicide rate among gay teens and some evidence for high pregnancy rate among young lesbians, sterner measures are necessary to dramatize gravity of situation.

Dimensions of holiness

This leads me to look by way of conclusion at the dimensions of holiness that shape our agenda as we challenge the churches of which we are a part. I phrase it this way because I believe there is enough work to go around. I no longer see this as we/they, us against them, conservatives versus liberals. Of course there are some dimensions of this just as there is a real difference between Al Gore and George Bush, make no mistake. But in our circles, I see no strategic nor spiritual percentage in siphoning off energies and people when we’ve only just begun, when the justice at stake is sexual and much more, when backlash is so pernicious but also a sign that we are making real progress. Likewise, I am leery of spiritually that is divorced from such reality. To me it is dangerous emotional fluff that can mask the real issues at hand and obscure the presence of the divine. In fact, I now see some danger of this already when I read the history of our glbt movements in various religions. Remarkable as it may seem, there is little to do with God, Goddess, the Divine in any of it. Of course there are those who speak of a Judge, Rule God who decrees heterosexuality, but their pitiful analysis hardly holds water. Rather, it is mostly the history of people struggling to make sense of new behaviors, commitments and experiences that focus not so much on sex as on love. As I will preach here on Sunday morning, I think the movement we are about can be characterized in Pauline terms as an “overflow of love.” It is this dimension that alerts me to the fact that we are en route to holiness as we struggle for queer justice. So what will that holiness entail? Because I believe it is of God, I think we can see it in tandem with the beloved world we enjoy.

Thus I return to our context for clues:

1. Globalization

2. Economic inequality

3. HIV/AIDS

4. Violence

5. Religious Pluralism.

(1) Queer holiness is global in all the ways globalization is not. It begins in the particular culture, language and customs of people around the world. It takes a range of forms; one size does not fit all. Some will dance, others sing; still others will make love while a group will mediate. But all will share what I posit to be the heart of spirituality, attention, holy attention to the divine, one another, our animals and planet.

(2) Queer holiness is expressed in the radical sharing of the earth’s goods with the earth’s people that marked the Jesus community and so many other religious groups. It is a rejection of post-industrial capitalism’s stranglehold on the world, and a commitment to economic reordering as an essential religious practice.

(3) Queer holiness is expressed by an attentive response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Whether prevention strategies beginning with condoms, pressure on drug companies to share the wealth of life-enhancing and prolonging drugs, or facing the social and cultural realities that make HIV/AIDS an unequal opportunity killer, queer holiness acts up.

(4) Queer holiness is non-violent in the most profound and far-reaching sense of the phrase. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day and the Madres de Plaza de Mayo are among the many models of non-violent social change that works because it is powerful love.

(5) Queer holiness is religiously pluralistic, and pluralistic in expression within any one religious tradition as well. It is crucial that we hear especially from young people and let them shape some of the religious agenda, as many them are not as set in their ways as we are in ours. But religious diversity is not optional; it is given according to Diane Eck. What we need is pluralism: “pluralism will require not just tolerance, but the active seeking of understanding…Pluralism is not simply relativism. The new paradigm of pluralism does not require us to leave our identities and our commitments behind, for pluralism is an encounter of commitments. It means holding our deepest differences, even our religious differences, not in isolation, but in relationship to one another. The language of pluralism is that of dialogue and encounter, give and take, criticism and selfcriticism. In the world into which we now move, it is a language we will have to learn.” vi I couldn’t agree more.

Conclusion

I understand the continued antipathy on the part of the so-called secular queer movement against religion. Our track record has been dismal. But I wonder, with this approach to queer justice and holiness if perhaps we will get another hearing. I hope so because I think we have something unique and important to contribute to the moral flavor of our culture and in turn to the richness of our religious tradition. Besides, ready or not, queer we come.

i Jonathan M. Mann, “Health, Society and Human Rights,” The 1994 Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality, Harvard Divinity School Bulletin, 23:3/4, 1994, p. 10.

ii. Diana Eck, “Neighboring Faiths,” Harvard Magazine, September-October, 1996, p. 40.

iii. Eck, p. 44.

iv Sarah Ivy Gibb, “Pastoral Care with Transgender People,” unpublished paper, Harvard Divinity School, 2000.

v “Family, Marriage and ‘De Facto’ Unions,” Pontifical Council for the Family, Rome, July 2000. vi Eck, p. 44.

Mary Hunt Response to Questions

First of all I want to thank all of you for both your attention and your grappling with this rather extensive agenda that I laid out this morning. You know, the hardest thing about these kinds of conferences is sitting in your own office trying to figure out who will these people be, and what will their needs be, and where will their commitments come from, and so of course I read everything that people send me. I’m one of those people who reads cereal boxes, you know, so… But I read all the materials and tried to get all the information that I could about this group, but that is the hard thing, trying to figure out where to put an emphasis. And so what I’ve tried to do today is to literally cover the waterfront, in terms of trying to express the seriousness with which- not to say that there isn’t a playful dimension of this- but the seriousness of what we’re about, and the scope of it. Because I think sometimes we go away from these conferences and we’ve had a real good discussion about sex again, or not sex again, as the first question indicated, but I think that it’s very very difficult to really, especially for people who’ve been at this a long time, to figure out where we are now, what’s new, where we need to be going, and that’s what I tried to do this morning. So for people who’ve been at this awhile, it would be a challenge to them as well for people who are coming on board.

This is where we’re coming on board, and I think it really makes a difference if you’re coming on board now, or if you came on board thirty years ago. And that’s what I’m trying to do, and so I really appreciate your grappling with it. And you can take [the text of my presentation]perhaps as a study document, or however you’d like to use it with your own groups.

I’d also like to announce that Beverley Wildung Harrison, a colleague in ethics of mine, will be here in February, and I want to commend her to you and you to her, because I think that many of the issues we’re discussing this weekend, she will be dealing with from her considerable wisdom. She’ll be discussing recovering the body of faith. She is an expert on Christian sexual ethics, so I want to just recommend that you come to hear Beverley. You will not be disappointed.

1. I want to start with a couple of the latter remarks and then go to the earlier questions. I want to start with the woman from China who asked about the personal dimension of this work. And I appreciate your question very much, because this presentation was not grounded in that since I had done a lot of that, well some of that at least, on Thursday night, trying to describe where I come from. But I want to make just a couple of personal comments about why I see things this way now. One of the reasons is that I’ve been doing this for a very long time, as have many of you in this room, and I have seen, and I said this on Thursday night and I’ll say it again, I have seen enormous change, and I know that there is a lot more change to happen, and I know that there is not change everywhere, but I have to say, personally and within my own family, within my own community, even within my own religious tradition of Catholicism, I have seen enormous change in thirty years. And I think that having said that, I would be remiss if I didn’t keep pushing myself as well as other people on this.

And so I say that happily, but I say it also uncomfortably, because so much of what I have seen and experienced is related to my being white, and to being well educated, and to living in the U.S., and to living in a city, and to living in a middle-class, mixed neighbourhood. In other words, there are a lot of factors that give me that perspective, that do not accrue in the same way to other people. At the same time that I’ve been struggling with these issues, I’ve also been struggling with the other issues that many of you are involved in, especially questions of economics and anti-racism, and so forth. And I see these issues as deeply related. And I’ve tried to do some of the analysis of that. There’s certainly more if you want to come back with more questions. But I can’t do one without the other. And from a strategic point of view, I’m really excited strategically to be able to engage people who are dealing with other issues on this queer issue. In other words, people who are working on questions of people who are homeless. Who do you think is homeless? A lot of transgendered people are homeless. A lot of queer kids are homeless. A lot of people of colour are homeless. In other words, once you… I want to have an entree to those people who are working on questions of homelessness around this issue. And If I’m going to have that entree, then there has to be reciprocity. I have to be working on their issue as well. So there’s a strategic as well as an existential reason for this, at least for me.

There’s also a lot more to be done, especially around the issue of children. And when I brought up the question of adoption, that’s a very real issue for many of us, and for women and men around the world who want to deal with this question of there being children out there who do not have families, and yet to have a document like the Catholic one I quoted this morning, be promulgated a few weeks ago, says we’ve got work to do. So that’s where I come from personally.

2. The other thing has to do with the question of sexuality, and I really am rather libertarian on a lot of the sexual questions. I really, I’m one of those people who feels as long as you don’t scare the horses, you know. But I’m very serious about, and this goes to the questions from the gentleman about violence and male privilege, I’m very serious about what happens for most women. Which is that sexuality is fraught, not because of the kind of guilt issues that Richard was raising yesterday, but because of the issues of power, of danger, of coercion, of disease, and of economics. And so when I talk about pleasure as a human right, and by the way, there is a Chinese woman who has written in this volume Good Sex, in which my essay is set, Dorothy Ko, has written also in that book. She was born in Hong Kong. And what we’re trying to talk about in that book, and what I’m concerned about, is pleasure as a right. And it is not pleasurable to engage in sexual activities if you feel unsafe, if you’re coerced, if your health is in danger. And so I’m trying to move from women’s experience. Also because of the number of women who have been abused or who have been incested or who have had difficult experiences around sexuality. There really is a different starting point for most women in this culture than for most men. Which is not to say that men have not also been incested and abused and so forth. But the power dimensions that were so rightly named in terms of white male privilege, I think are real.

3. I also want to talk about the question of touch, because I think that the comment on touch is very well taken. That touch is something that is very culturally coded, and that the way in which we understand touch, and even distance, how closely we move toward one another, how closely we sit next to one another, how freely we feel we can kiss one another. We were talking last night over dinner about the Argentine case where, you know in Argentina where everybody kisses everybody when they come and go, and it doesn’t matter if you know them or not. Well, heaven forfend you would do that here. I remember, I just spent a year in Argentina, and I went back to visit my parents in Florida, and my father presented me on the golf course to one of his buddies, and I immediately kissed him. Because that’s what I would do in Argentina, with anybody, and so I think my father felt, well, my goodness, what gives here? Hope sprang eternal, I must say. But these are very culturally coded things, and they’re also things that we need to learn to talk about. Because touch can be both healing and offending. And even in our religious services sometimes when we invite people to hold hands, or to greet one another, and we’re unaware of the way in which damaging touch has affected people, that becomes a very serious problem and many women who have experienced abuse have brought that to our attention. So those are just some of the personal issues that I think help to structure for me at least, some of my concerns around this.

4. I want to go back to the question, the first question on sex and religious communities, or what we call sex and the single nun, or … I have, some of my best friends are in religious communities. In fact my partner was in a religious community for many years. But I think you’re right, that in women’s religious communities, and I assume by that you mean Anglican or Roman Catholic religious communities, I think there is a dearth of conversation about sexuality, which is in some ways the same and some ways different from the conversation in other settings. One of the ways it’s the same is that a lot of people don’t talk about sex, but in another way it’s very different. Because the price of not talking about sex in a woman’s religious community is at issue. If you do talk about sex in a women’s religious community then you’ve obviously had some experience to talk about, and if you don’t, you’re sexually suspect. So I mean, you’re sort of caught either way.

I think the issue is very similar to what happens in the churches in general, which is duplicity around this question. That we lie to each other, either by lies of omission or lies of commission, in terms of what we say. And I think that especially in women’s religious communities the tragedy is that if you’re building community and trying to resemble family with people, and these fundamental things you can’t talk about, there’s a terrible contradiction. And I think in the Roman case where celibacy is enforced from on high, I think this conversation, or lack of it, becomes a kind of expression of kyriarchal or patriarchal power over women. And that it divides and conquers women one from the other. And especially now that we know that in many religious communities, both male and female, there’s a very high percentage of people who are gay, lesbian or bisexual, and I think that that’s another piece of the problem. But in general, I think, we’re better at talking about sex than money. Most of us. It’s easier to say whom you recently had sex with than what your portfolio’s worth, or not. And so I’m also a little leery of letting sex be the sort of dominant discourse in any community, because I think that it lets us off the hook about a lot of other things. We think, it creates a kind of false intimacy too. We think that if some people know something about us sexually, they know more than we, they know a lot. And in fact your portfolio or lack of it would probably say more.

[piece missing] her heterosexuality had been obscured from her, as a woman, that her heterosexuality had been obscured from her, and I think that for many women in religious communities, that is something to talk about. It’s not the sex, it’s the fact that it’s been kept from you. To even understand your sexual identity. That’s a human right, and I think that’s where I would go with it, not the sex qua sex, but the right to have any conversation you want to have. It seems to me it’s an issue of power.

5. G’s question about the categories and the need for identity, that’s a very tough one because it’s so new. You know, you and I, we’ve been in the women’s movement for a long time, and I’ve been out as a lesbian for a long time, and I’m not questioning those things in a fundamental way, really. I mean, of course I am, and I’m trying to help you and others to do that, but I guess the issue for me is not identity, but solidarity. So that it’s not so much, for me, it’s not so important who I am, but what my commitments are. Because the who I am kinds of things can change. But fundamental commitments of solidarity, it seems to me, deepen, and that’s really, for me at least, it’s the way to go. It’s not the identity politics, I don’t care if you’re a straight white male, as long as we’re moving in the same direction. Come with me, brother. I mean, that’s my attitude, and I think that there were times and there are times when separatism and discrete identity categories become very important, and especially for people who are marginalized, but for the most part I think, it’s the question of your solidarity, not your identity, that I think is at stake. I hope that’s helpful.

6. A similar question came after that, which was the question of, I was talking sort of at the macro level, especially around religions, and what about the microlevel. Does this mean now that it’s not important to be an Anglican, or it doesn’t matter if you’re a Catholic. Yeah, obviously it does. But in the same, and Rosemary Ruether I think, helped me see this best. She said “You know, I’m a Roman Catholic because I was born there and brought up there, and so my primary obligation is to be like a fly on the back of the Roman Catholic horse. And if you’re Anglican, then you need to be a fly on the back of the Anglican horse.” And I think that’s right, that that becomes a primary responsibility, and also a community of accountability, because people speak the same, at least a similar language, and have a similar spiritual flavour, if you will. But then I think this larger question of pluralism really becomes very interesting and compelling, because there are people who have similar takes across those traditions. And there are deep differences within.

And that was another one of the questions that arose. Why don’t they get it? The fact is that there are probably more similarities now. You know, we used to divide religions like this: these were the Anglicans, and these were the Catholics, and these were the Methodists, and these were the Muslims. But now they really go like this, in terms of progressive Anglicans, and progressive Catholics and progressive Muslims, and so forth, working together on this plane, and those who are conservative making another kind of alliance. So I think that the religious changes, the religious shifts are now much more from discrete denominations to this kind of horizontal plane where lots and lots of people from different traditions can form what I’ve long called “unlikely coalitions” of justice-seeking friends. It’s rather unlikely to be working with people whose language or traditions you don’t share, but if you’re moving along on the same issues, then I would take HIV/AIDS as an example of that. It seems to me much more realistic than trying to do that within your own tradition. So in some ways I’m talking about a theo-politics of necessity as much as anything else.

8. With regard to God, just going down my list here, you know. I said in my lecture, and I would have to say it again, that there’s precious little in the literature, and this maybe is where the work most needs to be done. On this question of the Divine, or God, with regard to queer theory, the closest thing there is is Robert Goss’s Jesus Acted Up, where Bob talks about using a liberation theology model, a God who is one with the oppressed, so we had a God who was black, or the Divine who is female, and this sort of rhetoric of liberation theology, which I happen to share. I think that’s a very useful first cut at the problem. I don’t know really, what to say about God in this regard, except to say that for me at least, and these are always very personal kinds of takes on issues. But for me, the presence of the Divine, the notion of the Divine being on the side of those who are oppressed, the particular presence of God in the struggles for justice, is richer and deeper than ever, out of this perspective. I have a deepened sense of my own oneness with that Spirit that I talked about on Thursday, that really functions for me in a very everyday way. And I don’t really have much more to say about that, and I guess a theologian ought to, but, call someone else. Call me next year, and, again, I think this is the edge of where we need to go. We need to now provide, out of this pluralistic context, some things we can say. And maybe the best thing we can say at the moment is the silence that I invite as well. I think many of us who meditate and who find in the contemplative dimension of our various traditions a touch where the Divine have something here to contribute, but I’m only at the beginning of that road, so I will have to say some more about that another time.

9. I want to acknowledge the question on ableism and sizeism, and you’re absolutely right. Neither one of them were involved in what I said this morning and both should have been. So I want to stand corrected and assure you that they will be there, thanks to your good insight, down the pike.

10. Whether churches grow and change or shrink, resist and shrink, the questioner is absolutely right, that there’s an enormous body of evidence that shows that the more conservative churches are on the upswing, and the more progressive churches are losing numbers. And I think that, I don’t dispute that at all. In fact I lament it. At the same time, I have to look historically, and say that over the long haul, it’s sort of like if you invest in the stock market and you just watch what happened yesterday rather than you look for thirty years at how things go. I think in theological terms, that we think in centuries and not in decades. And I think in the last two decades what was described as true, especially the evangelical Christian churches have grown geometrically, and some of the more progressive churches have shrunk. But I think over the long haul, I’m not persuaded that’s going to be the case, and there I could be wrong. But I think of groups like the Shakers, for example, who, well, they resisted and shrank around some sexual issues. So, you know, there’s some of that. I’m not sure.

I have to say I may be wrong on that, but I think over the long haul, and that’s why I think some of us are still working on these issues, in, for example, the Roman Catholic church. The Roman Catholic church has changed enormously, and grown. Not that I’m altogether happy about that, but it has changed enormously, in the direction I’m talking about, despite the document that I read. The fact that the Roman Catholic church has to spend seventy-six pages talking about people engaged in primary relationships that are not heterosexual monogamous marriages open to children, says that we have had an enormous impact there. And that church is growing. So I’m not sure. I’ll leave that one. I think the jury’s out on that.

11. As far as stealing my ideas, it’ll be on the web shortly. There’s not much private any more. But I think the larger question that was behind that was what kind of move this body wants to make in terms of a statement to the Anglican church. And there, anything that I’ve said that may be helpful, you’re more than welcome to, and I think you just need to decide what you want to say.

12. Finally, the question of “trickle down.” I don’t know the answer to that question, but I have at least one guess, and that’s called children. It seems to me that one of the things that happens is that as successive generations deal with these questions, it seems to me that the change takes place in a very deeply rooted way. And it happens because most people’s children’s experiences are very different from their own. That’s part of what we’re dealing with here, in terms of the generations of people, those folks who started in this movement quite some years ago, and folks who are starting now, starting in very different places. And I have great hope in that. I also think the Anglican church may be in for a bit of a fray the next ten years or so, but I just don’t think you can hold the line against something that’s so clearly rooted in the life of the Spirit. I may be quite naive about that, but I just don’t think you can hold the line much longer.

13. And finally, in terms of globalization and international questions, I think that the presence of people from other countries here, especially our colleague from Africa, and some of our friends from other places, show that we’re already in a globalized experience in justice-seeking. And that’s what I mean by globalization in a positive way. And I think it has to be, it can’t be over-emphasized, in fact I was sorry that the international workshop here didn’t happen as it might have, because I think what happens to us is now what happens internationally. It’s not what happens in the U.S. or in Canada.

I want to thank you again. I hope this is a helpful first take on some of your comments, and I’ll be around the rest of the weekend, and so I’ll look forward to hearing more from you. Thanks again.

Richard Holloway: Response to Mary Hunt

I’d like to offer a couple of purely, kind of personal subjective responses to the magnificent lecture that we heard from Mary earlier this morning. I mean, I was simply in awe of its majesterial sweep and the moral intensity of it. I mean, I’m a junkie for great talk, and this was magnificent oratory. And I find myself in total agreement with its moral passion and indeed with its ordering of priorities, because leadership is always about priorities. There are always choices to make. One of our British politicians, one of our more intelligent British politicians, said that in political and intellectual discourse, you never reach conclusions but you have to make decisions. And decisions are about choices, they’re about priorities. And there’s no doubt at all that we were given an enormously passionate project in the quest for global human justice, and that will involve us in making choices. Sometimes awkward and difficult ones where there will be a conflict between rival groups, but we can’t go down both roads at once. And old Frost said it, sometimes you have to take the road less travelled by, and that can make all the difference.

But let me now offer a kind of summary reflection, because I was asked if I would use this time as well to make a kind of response, not only to Mary’s wonderful paper, but to the whole few days that we’ve had together. The first thing I want to say does come however, from my listening to Mary’s paper. It reminded me very much of the last, and I think the greatest of the Hebrew prophets, Karl Marx. The prophet Marx, his single greatest diagnostic insight, and the one that is most enduring, is that power always justifies itself, not only with muscle and bomb, and it will do that, but also with theory and with ideology. And those are much more subtle and insidious, that the people in charge of things defend their position at the top, their hegemonic rule, they defend it not only with muscle, but with theory.

And it happens to all sorts of concentrations of power, including theological and ecclesiological, as well as economic power. During the debate on the ordination of women in the Anglican church, when the guys were opposing it, they didn’t say, “Push off, women, we enjoy being in charge, we want to be in power.” They said, “We’d love to have you in, sister, but it’s, it’s God. It’s the tradition. It’s in the scripture.” They offered ideological justifications, always by theory. And it happens, and it’s happening with the defence of global capitalism. I came across a brilliant example of it in G. K. Gowbray’s little book On the Good Life, in which he, and he’s not a wild radical, he’s actually more a reformer, he thinks global capitalism is here to stay, but at least let’s try and humanize and mend it. He says a very interesting thing, he offers a very interesting insight here as to the way the people and power organize the thing to suit their own ends. He says that global capitalism, capitalism, the market, has two effects. One is inflation and the other is unemployment. These are two intrinsic effects of the system itself. But he says the people in charge of the system suffer more from inflation than they do from unemployment, so they order the system to combat inflation, because the people that pay through the other consequence of unemployment are of course, the poor. It’s the rich that suffer from inflation, and so they manage the system to moderate inflation, and that’s the single most potent economic plank in my own government’s economic programme is to keep inflation down. And of course, it does militate against the people at the bottom. And they have great campaigns to bring people into work, but the work they’re bringing them into are insecure, low-paid jobs with no securities at all. That has become the new economy. So, I think it’s important to remember that Marx continued the prophetic challenge to power that is begun in the Hebrew scriptures.

And Jesus was in that tradition, and it seems to me that one of the things that theologically we need to recover, and I’m going to be preaching about this, and this is not a commercial, I’m going to be preaching about this at the Cathedral tomorrow. One of the least promising parts of the New Testament material is called apocalyptic, it’s the kind of stuff we read about during Advent, this season, about the end of the world, about the supernatural intervention of God to right the wrongs of an unjust creation. John Dominic Crossan, another brilliant renegade Catholic, they’re a wonderful breed, has said in one of his books that apocalyptic is always the religion of broken people. If you have a passionate commitment to the meaning of God, and you see your children starving and your people oppressed, you ask why. And the longing for justice, the paradox of a righteous God permitting this kind of institutional and systemic injustice to continue for another minute, becomes the parent, the mother to the thought that something is going to happen. God’s going to do something about it, and that becomes apocalyptic. God will do something about it. The end will come. The Messiah will return. Justice will flow down like a river, and the whole creation will be mended and cleaned up. And Schweitzer, the great New Testament scholar who gave up theology and went and became a missionary doctor in the Congo, believed that Jesus was a disappointed apocalyptic because he thought that one more push and he would bring in God’s kingdom. But as he says, and his language is as good as the King James version if you like that old-fashioned stuff, he said Jesus tried to push the wheel of history. It rolled back and crushed him, and he’s hanging upon it still.

It’s very difficult material for people to use today, unless you happen to be a fundamentalist, and you think you’ve got the key to it, and so you go to the Holy Land to wait for Armageddon to come, and there’s a lot of that stuff. I think the way we use that material is to make it into a realizable political ethic. Because the world is unjust. It just isn’t good enough. God’s kingdom has to be forced, has to be brought to pass. And I think that what we had this morning was a marvellous eschatological programme, a new apocalyptic ethic for a mended creation. And the thing that you have to remember is that you never ever actually bring it in, but you to keep on going after it. Marx as a predictor was proved false. As a prophet of hope, he is eternally justified. And it seems to me that what Mary gave us this morning in her five-point apocalyptic programme, if I may put it like that, she told us that we have to pay attention to the new revelations.

There are new ways that we’re discovering that humanity is configured. They’ve always been there, but we, they’ve only now been given the courage to say who they are, to assert their visibility. We have to pay attention to the Divine commander, and my definition of God is that to which you radically and sacrificially respond. It’s an absolute ethic. The American pragmatist philosopher Pierce said that a belief is a habit of action. If it isn’t, if it’s simply something between your ears, it’s a waste of time. But if it is as the scripture operates, if it actually challenges you to transformative life-changing action, then you’re responding to the Divine. You can call it the Divine, but if it’s simply you justifying your sexual power, your gender power, your economic power, then it ain’t God. It’s your own lust and greed and human gluttony. So we pay attention, especially to the new voices from the edge.

And there has to be, I think, and this is probably the greatest and most complex challenge, because we’re all implicated in global capitalism, and Mary has made that very honestly clear. But there has to be a new challenge to it, to the effects that it’s having. It has disproportionately terrifying effects on the poor. And I know that you see it at its most extreme in the United States which doesn’t have anything like even the shreds of a welfare programme, but even in Europe where we have elements of a welfare programme, the poor are terribly at risk. And of course, we now live in a global village, and the movement of capital simply at the press of a button can have devastating effects on say my own border’s region, where our cashmere industry was almost wiped out overnight because of the banana war in Central America. We are implicated with one another, and what we have is a system that is not susceptible to national governments’ challenges. And the human community therefore, has to get together to do something about it.

I don’t know how we’re going to do it, and that’s why I resonate to some extent with the angry challenges against capitalism. But we need thought-out challenges, not simply gut, intestinal responses, but clearly defined. We need to recruit the good progressive thinking economists, people like Galbraith and the new young ones that are coming up, because the system is enormously powerful, and immensely destructive, but it also could be harnessed for good.

Mary’s absolutely right. The single most imposing human catastrophe in the world today is the HIV and AIDS pandemic, not only in Africa, but particularly in Africa. In many ways it’s the paradigm offence of power, and it’s tied up in so many, many elements in Africa. It’s about sexism, it’s about the drug companies, it’s about global capitalism, it’s about sheer obscurantism of the sort that you find in Mr. Umbeckie’s refusal to accept. What science actually says about the condition itself, that too has to be part of this new apocalyptic ethic. It has to be non-violent, she says.

Non-violence is much more thorough-going and difficult than simply not being physically violent. I think most of us would find the non-physical violent bit easy. I’ve long since lost the urge to punch anyone in the nose. I used to have a wee bit of that in me when I was a youngster, but I’m more likely to be on the receiving end of a harder punch if I tried it now. But I think we ought to go deeper with it, because there is an intense heightening of verbal violence in our culture. And I’m as guilty of it as anyone. Well, maybe not as guilty as some, but I do get tempted sometimes to indulge in kinds of insults.

Now, I’m not saying that we can’t argue robustly, that we can’t challenge prophetically, and even angrily, but I do think that the challenge to be non-violent goes very deep into our own psychology of protest. And one of the most astounding things about Martin Luther King was that he managed even verbally, to be non-violent. I’ve always found that kind of difficult, because I’m a kind of a passionate punchy kind of person, and I tend to trip myself up.

The final element in this new apocalyptic ethic is that we do not tolerate pluralism, we celebrate it. It’s wonderful, the fact that we are the rainbow people of God, that we’re all different, all different sizes, all different sexualities, and I was absolutely gob-smacked and baffled by this new trans-g stuff. You know, we don’t have that in Scotland. Although the men have been wearing frocks for years called kilts. But they’re not allowed to wear underpants, so you can easily tell what they are, by just shoving a mirror under them.

It is an astounding programme, and it’s the fear of the different and the new that is behind all of the kind of stuff that you’re so [sits?] in the church, all those frightened men in all the churches, and I say men because they’re mainly frightened men. And yet, if you could somehow get them out into the open air, into the marketplace, it’s a wonderful world. We are an astounding species. We’re immensely creative, we’re so different, and difference is wonderful. So go for Mary’s apocalyptic ethic. Prioritize. Make choices. And enjoy yourselves as you do it. And thank you very much.

Loving Justice Conference Plenary Notes

Church of the Holy Trinity, December 7-9, 2000, Toronto, Ontario

For individual use, reprinting requires author’s permission