Loving Justice Conference Plenary Notes

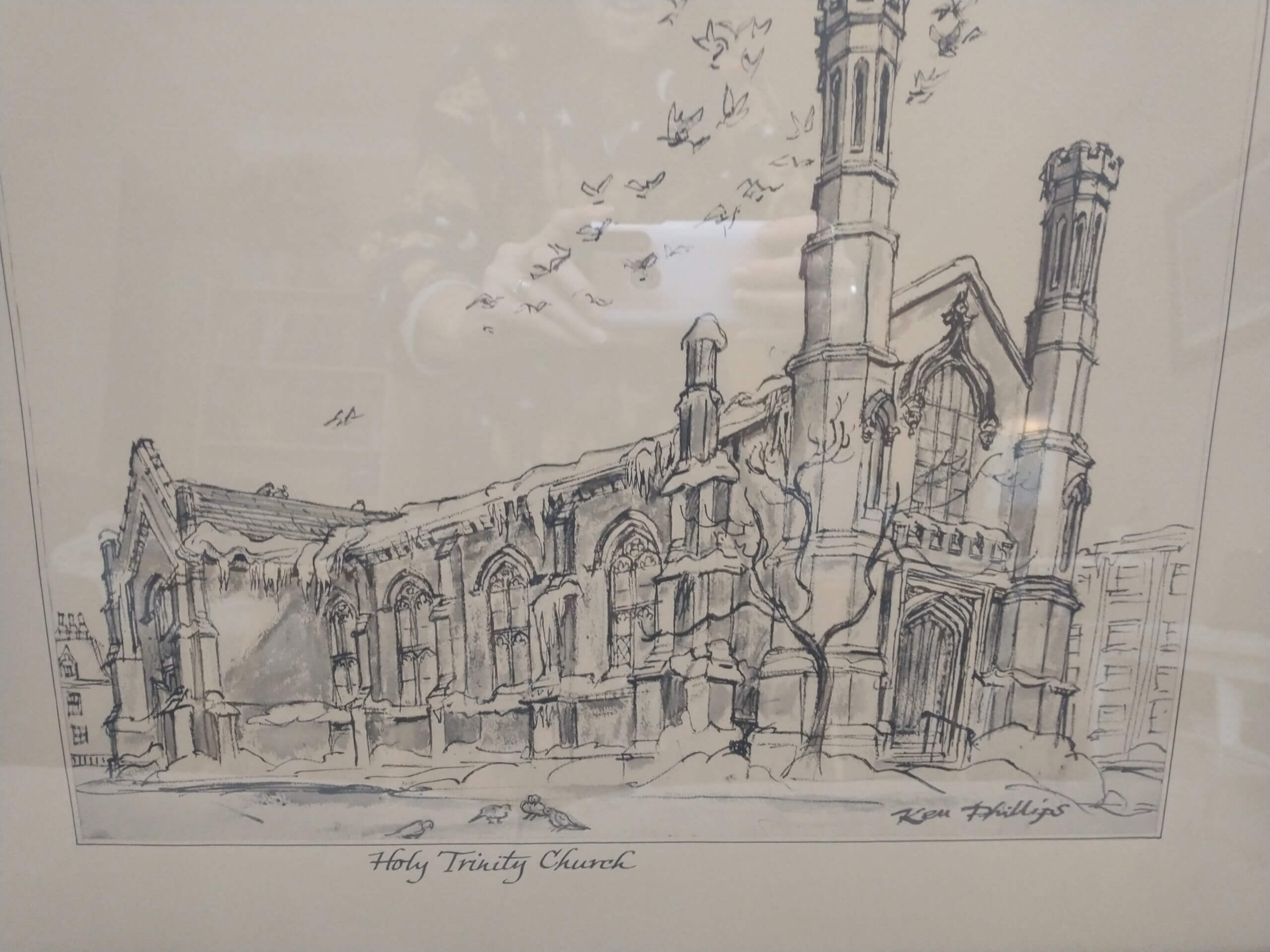

Church of the Holy Trinity, December 7-9, 2000, Toronto, Ontario

For individual use, reuse, publication or printing requires author’s permission

Keynote Address – Richard Holloway

“How We Got To Where We Are: Three acts and an epilogue”

Do you know, sometimes your computer tells you that you’ve shut down illegally, and you get that kind of blue screen when you start up again and it says in case you’ve corrupted all your programmes you have to press any button on the keyboard, and also some things flash and you get this racing checking of everything. I’m going to do something a bit like that this morning, or another image might be one of those helicopter rides you see in thriller movies, when they’re kind of traversing a whole city or a whole country. I’m actually going to cover a lot of terrain very rapidly. I’ve called this presentation “How We Got to Where We Are,” and I think of it as having three acts and an epilogue, and I’m actually going to range over the whole of the history of the universe. It’s a slightly ambitious task, and I hope it makes some kind of sense, and I’ll try to finish it in forty minutes. But it’s asking quite a lot.

THE VIEW FROM NOWHERE

So, let me get into my three acts, and the first one I’ve called “The View From Nowhere,” and what I want to try and do is to set the scene of the origin and history of this extraordinary universe that we are latecomers in. We know now that the narrative of our universe is unimaginably vast, its history is immeasurably long. We know that for billions of years, there was a universe of inert matter, emerging from that explosive moment out of nothingness that the physicists call a singularity. Now, I’m not going to get into any kind of arguments of design for the existence of that being or non-being, I’m simply wanting to stand under and express the sheer miracle that there is something and not just nothing, that out of nothing this extraordinary universe exploded within microseconds, and just blasted its way through the universe. It is an unimaginable history. It’s the great scientific narrative of our time. And it almost eclipses the wonderful myth of Genesis. It is in its way mythic, epic, in the picture that we have. It could have crumpled back into a black hole, but the tension between expansion and gravitation spread out the universe, and it’s still blasting a way into outer space. And from that inert matter exploding into space, chemistry gave us a soup of a sea, and from that sea emerged self-replicating molecules – LIFE. Because the secret of life is self-continuance, self-replication, and from that churning, bubbling chemical soup, at last some kind of self-replicating life emerged. And the very beginning of the possibility of us.

And after about fifteen billion years of this unimaginable slow cooking, we emerged, consciousness emerged, the ability of the universe to think about itself. I don’t know whether it’s going anywhere else in the universe, or whether only on this microscopic dot of part of a tiny subsection of a tiny galaxy is it happening. And that we, at last, in us, the universe is thinking about itself, has become intentional, has actually started looking at itself. The sea is in our veins, and consciousness is our greatest glory and our deepest affliction. The mystery of the emergence of consciousness is the great scientific task of our era. I don’t want to get into any of that, I don’t really understand what the new neurophysicists are talking about, but it is the most extraordinary miracle, and it’s us. We are that miracle.

And one of the consequences of this emergence of consciousness is that the universe is now in us, self-conscious. It’s now watching itself doing what hitherto would have been done, as it were, unselfconsciously, because consciousness did not exist. So we have moved from instinct, almost automatic movement of the life force itself, to intentionality, to the struggle with our own instinctive drivenness. The vast history, the fifteen billennia behind us, in us is now thinking about itself. But it’s also struggling with that great weight and surge and thrust of the history of the universe. Nietzsche saw all of this as the emergence of what he called humanity’s sick conscience. But in us, what hitherto simply happened, the life force banging and thrusting and vulcanizing its way through time, in us is now thinking, and thinking casts a kind of pall over action. That’s why we are hesitant, confused creatures, because we’re now, as it were, caught in the act of our own instinctive life. That is the kind of first traverse that I want to offer you, the first act, as it were, in this extraordinary drama that has produced us, and our activity here this morning is a part of that ongoing drama.

A FEW MILESTONES

1. Forest to cave:

Let me now move into my next act, and offer you a few milestones in our development as humans, as creation become conscious, as the universe thinking about itself, as the life force becoming intentional and not just automatic and instinctive. These are guesses, because who can penetrate to our earliest days, our earliest years as a species, but great thinkers have come up with one or two ideas, and one of the ideas that was produced by the Enlightenment historian Vico, who was one of the first, as it were, historical scientists, one of his guesses is that when we moved from forest to cave, significant changes in the way we ordered, organized and thought about ourselves resulted. He saw the move from the feral hunting life of the forest to the steadier life of the cave as the emergence of the family state, and the beginning of the ordering of sexuality, and he suggests that we moved from free-range sex, whatever that might have been in those dark forest dwellings, we moved from free-range sex to the possession and ordering and mastery of sex, probably by the head of the cave unit.

2. Origin of religion:

The second little milestone in this extraordinary development that has resulted in us, is related to the emergence of religion and whatever that means. And again, Vico has a guess at it. Nietzsche has a guess at it. For Vico, the origin of religion came in the fear of those cave dwellers as they listened to and were oppressed and frightened by thunder and lightning. There’s some evidence from cave drawings that they associated thunder and lightning with oppressive forces, and so the first, the earliest religions were placatory religions of augury and appeasement. This sense of bafflement, I can’t actually enter it, but can you imagine the kind of mix that’s going on as you’re actually beginning to think about, you’re beginning to get self-conscious, you’re in this dark, thunderous reality, lightning and thunder, and the instinctive, primitive reaction is to objectify and identify it in some kind of personal way. Vico saw that as the emergence of the frightened anxiety-driven religious consciousness.

Nietzsche came up with, in many ways, a more Freudian and a more subtle interpretation. He saw the origins of religion in dreams. And let me quote something from Human, All too Human. You know that Nietzsche wrote in paragraphs and in aphorisms, and this one is called “Misunderstanding of the dream.” He writes:

In the ages of crude primeval culture man believed that in dreams he got to know another real world; here is the origin of all metaphysics. Without the dream one would have found no occasion for a division of the world. The separation of body and soul, too is related to the most ancient conception of the dream; also the assumption of a quasi-body of the soul, which is the origin of all belief in spirits and probably also of the belief in gods. The dead live on; for they appear to the living in dreams; this inference went unchallenged for many thousands of years.

Take your pick. But we have this picture of these primitive crouching cave-dwellers developing religions of augury and appeasement, cruel religions, and there is a lot of evidence that a lot of primitive religion, not all, but a lot of primitive religion is deeply cruel and placatory and appeasing. There are solid echoes of that as we heard from Mary last night, in the Christian atonement tradition. And the next element in the complexification of human structures was the solid emergence of patriarchy, and the father became the source of value and the possessor of the sexual dynamic. That’s my second milestone.

3. Gradual complexification of society:

The third milestone in this second act, because I’ve swept over the terrain in a general way, I’m now, as it were, trying to focus down with more contrast and exactness on the emergence of the human. And if we can at least see in some kind of sketchy outline, the beginning of religion, the beginning of the family state, the beginning of the possession of sexuality by the patriarch, the head of the cave unit, then we begin to see those elements in the complexity of our own post-modern human situation.

Another one of Nietzsche’s insights was that the gradual complexification of society made not only intentional, hitherto instinctive aspects of the life force, it actually interiorised the cruelty that exemplified the life force. Nietzsche had a great love almost for the fascist warrior, not the Nazi. That’s, I think, a libel against Nietzsche, but he did have a great admiration for the warrior person in his instinctive, and it was a male identification, the warrior person who simply by his instincts, survived, and conquered, and created value by his own power. One of his most seminal texts is called Beyond Good and Evil, and he maintained that the strong powerful warrior leader created value by what suited him, and by what helped him to endure. But in more settled societies, that ascendant cruelty, that ethic of pure power itself, becomes complicated, and interiorizes itself into introspection of what he called ‘the bite of conscience.’ Because if you can no longer express this ascendant cruelty of the life force, if you’re having to think of more complicated social arrangements, it begins to churn and bite inside you, and you interiorise your cruelty, you turn it in upon yourself. And this is Nietzsche’s great accusation that it takes revenge, but cannot be expressed outwardly; it takes revenge upon itself inwardly.

And the same is true of the sexual dynamic. The interiorization of desire, that which hitherto simply expressed itself, now is complicated and in a kind of an interior writhing. Let me read you something else from Nietzsche. This comes from The Dawn, and it’s called “Thinking evil means making evil.” And I think that this has particular potency for the Christian sexual problematic which is what I’m gradually going to come to, you’ll be glad to hear. There is an end to this. Nietzsche writes:

The passions become evil and insidious when they are considered evil and insidious. Thus Christianity has succeeded in turning Eros and Aphrodite – great powers, capable of idealisation – into hellish goblins. In themselves the sexual feelings, like those of pity and adoration, are such that one human being thereby gives pleasure to another human being through his delight…

This is Nietzsche, very gender-specific. Don’t blame me for the language, this guy was no feminist. But let me repeat that, because I think this is a central insight, and it’s a lovely one. “In themselves, the sexual feelings, like those of pity and adoration, are such that one human being thereby gives pleasure to another human being through his delight…”

And then this: “…one does not encounter such beneficent arrangements too frequently in nature.” The kindness of nature, that we can give delight to one another, through Eros. And then he goes on: “And to slander just such a one and to corrupt it through bad conscience!” To take this delight that we can give one another, and corrupt it with a bad conscience. “To associate the procreation of man with bad conscience!!” Double exclamation mark. Nietzsche is furious at Christianity, because it has made this dynamic of delight filthy. It has corrupted it. This beneficence of nature that enables us to gentle one another, to pleasure one another, to give one another delight, has become filthy, has become corrupted, has become associated with evil. And he goes on:

In the end this transformation of Eros into a devil wound up as a comedy.Gradually the “devil” Eros became more interesting to men than all the angels and saints, thanks to the whispering and the secret-mongering of the Church in all erotic matters…

If you read those great volumes of moral theology guides to the confessor, read Foucault, the great tomes that confessors got so that they could find out exactly the minutiae of your sexual trespass. Whether you actually woke up during a wet dream and enjoyed it. The wet dream itself – morally neutral. But if you happened to wake up and said “My God, this is fun,” off to the box the next day, because you have sinned. He goes on:

…thanks to the whispering and the secret-mongering of the Church in all erotic matters: this has had the effect, right into our own time, of making the love story the only real interest shared by all circles – in an exaggeration which would have been incomprehensible in antiquity and which will yet be laughed at someday.

4. Elements of the problematic:

Foucault calls this the emergence of the sexual problematic. Sex becoming ‘problem;’ not delight, not power that needs to be handled carefully, but the moral problematic of sexuality for, particularly, the Christian religion. It was one of the most fateful turns in the development of that subspecies of the human species, the Christian subspecies.

So let me touch on a few elements of the sexual problematic in Christianity. I hope you’ve got the general drift that this life force, this explosive reality, which in us has become conscious, which interiorizes and therefore complexifies, and brings with it all sorts of complicated understandings of what had hitherto simply been automatic, instinctive, the life force doing its thing in us, inevitably, because we are thinking creatures gets complicated. But there’s a particular addition to the complexification in Christianity, that Foucault called the sexual problematic, and that’s what I’m now wanting to focus in on. And I’m still doing all right for time, I’ve got another three days.

Let me now look at the sexual problematic, some of the elements in it. Let’s begin by admitting that sexuality itself is a prodigious power, like electricity. And electricity can be dangerous, it can be used to illuminate, to warm, it can go badly wrong. So we can begin by admitting that in complex, sickly creatures ridden with the bite of conscience, this is as likely to go wrong as anything else. And if you follow Murphy’s law, which is the Irish version of original sin, that if a thing can go wrong, it will, then you would expect this one to get mixed up and to go wrong. Another one of Nietzsche’s great intellectual play toys was what he called the tension, the struggle between the Dionysian element and the Apollonian element in humanity. Okay, we have defined ourselves now, as instinctual creatures driven by the life force, but also conscious creatures driven by our intentionality, our thought process, and the two are in a kind of struggle. Each is good, but the one complicates the other.

The problem usually lies in the over-correction by the rational conscious part of our make-up over the instinctive, passionate automatic part of our make-up. Why was it overcorrected in Christianity, and not in Greek culture? Foucault has a very interesting number of pages in his history of sexuality, which alas never got finished because he died. But he says some very interesting things. He says that for the Greeks, the sexual problematic was there, it was admitted, it could go wrong, it could get badly inflated and out of kilter, but for the Greek it was always a question of more or less, never a question of right or wrong, whereas in the Christian sexual problematic, it is deep about right and wrong. It’s not about a good thing maybe being slightly overextended, well you ate too much last night, or you drank too much last night, or you, I don’t quite know what an appropriate word to use in the sexual sphere would be in this august assembly, but I think you get the message, that even that you can have too much of. But it’s always a dynamic of more or less for the Greek, whereas with the Christian sexual problematic, a fateful added element comes in, of the right or the wrong.

5. Why in Christianity?

Why? What happened? What happened to load it in Christianity with such momentousness, so that we don’t complexify and momentify the other appetites quite this way. Okay, we may not like it when we get a bit flabby and we’re overeating, we way “Oh, dammit, I must diet again.” But we don’t moralize it, we don’t beat ourselves up psychically over it. We would like to fit last year’s bathing suit, but it lacks the intensity of the sexual problematic. Why did the Christian make sex such a powerful problematic?

1. Religions of the desert:

Let me offer one or two guesses. None of them original, and I’ll come to St. Augustine in a minute, and everyone blames Augustine, and he certainly had a lot to do with it, but I suspect it’s a bit more complicated than that. I think there probably has always been, in human nature and in the great religious forces, contrasts between religions of the desert and religions of a more settled, urban type. There is a kind of austerity about the desert, and we come from a Hebrew religious matrix, and there is a powerful austerity in Hebrew religion towards the possibility that our instinctual nature can drive us into idolatry. That is a solid and honest root. Hebrew religion did not make sex problematic, so something got twisted a bit later on, in Christianity. You can see the elements of it there, because you find the same thing in that other great religion of the desert, Islam. It too has a certain kind of austerity, a certain disciplined, almost military approach to the instinctive life. Maybe as a protest against Dionysian excess, a necessary reactive austerity against the other, because human beings very rarely get themselves into balance. We wouldn’t have all these self-help books about living moderately if moderation were easy. Aristotle wouldn’t have had to write all the stuff he did, on virtue being a mean between two extremes, and that the only good thing about marriage was that it produced virgins. And there was a strong eschatological sense of the early church, that if we could simply stop people having sex we would all die out, and the end would come.

2. Dynamics of disgust:

It was never going to work. I mean, as an evangelical programme it’s about as wacky as you can get. But there was a strong element running through the intense asceticism of certain aspects of Christianity. And you see it at probably its most virulent in St. Jerome, who hated the thought of marriage, but the dear man, because there’s always in Christianity a solid pragmatic undercurrent, we know that we’re dealing with human beings, and so there emerged the licensed approach to sexuality. Those that have not the gift of continence may get a piece of paper that allows them to have sex, two or three times in their life, only for the purposes of procreation. And the old prayer book marriage service said that. It had a very, very kind of denigratory approach to sexuality. I was instilled with the ideology of celibacy as a young theological student. When I got married myself, I felt that I’d opted for second-best. I hadn’t had the courage to be celibate. I hadn’t been able to kill my sexuality off. And I felt the fact that I needed to be sexually active as a kind of spiritual defeat, because had I been a really high-octane, holiness type, the type that I was brought up in my monastic childhood to admire, I would have been able to discipline the body, and kill my sexuality off, and sublimate it into works of love and heroic evangelical testimony. I didn’t have it. I wasn’t good enough. I had to settle for second-best. I had to get married.

And there is that strong undercurrent even in Reformation theology, which permitted the marriage of clergy, because of course, if you do have this high octane doctrine of virginity, of sex as the polluting virus that hands on original sin, then you will want to preserve your holy creatures, your hierophants, the ones who are set apart to be icons of the glory of God. You will want to preserve them from that. At the Reformation, they had the same doctrine of the sexual problematic as the undivided Catholic Church. They just didn’t think that men were capable of celibacy. In fact, I’m told that there is a Philippine Catholic sect that broke off from the Catholic Church, and they have an all-female priesthood. And I’m told that they had a kind of referendum when they were setting themselves up, and they asked the members of the church whether they wanted a male priesthood, a female priesthood, a celibate priesthood, a married priesthood, and they said “We would like a celibate priesthood, but since we don’t think men are capable of celibacy, we want a celibate female priesthood. And there’s a certain amount of pragmatic sense in that.

The Reformation more or less accepted the going doctrine that sexuality was an ungovernable power, it would be better not to practice it, but we would license, we would offer license arrangements for it to be practiced, namely in Christian marriage, and we would insist that priests would be married. So that emerges the full-flooded Christian problematic about sex. And it’s only, I think, in our day, tottering to its end. Because there has been a Copernican revolution in our understanding of sexuality in our time. And we’re beginning to revisit the doctrine of the delight of sex. We’re beginning to talk about the unitive properties of sex, that it’s not simply about procreation, that’s in many ways, almost the least interesting thing about it, that it has an almost mystical ability to create friendship, to be a symbol, a sacrament of unity. These are the ways that we talk about it when we’re preparing people for relationships, when we’re guiding people through the breakdown relationship, this is the kind of rhetoric.

HOMOSEXUALITY

But let me now focus on the queer angle to all of this…

1. Four attitudes:

Let me jump to the chase on the gay thing, then, and I’m nearly done. I might finish by this afternoon. There has emerged, against all that background, a particular loading, obviously there’s going to be a particular loading about homosexuality, and there have historically been four, or there are four current attitudes in Christian theology to this way of being sexual, this way of expressing sexual delight. And I’ll rush through them. Punitive non-acceptance, stone the buggers. Many people would say that that, in fact, is the Biblical norm. Non-punitive non-acceptance, you don’t permit it, you don’t even legalize it, but you just don’t stone them. You take capital punishment out of the equation. Partial acceptance, which is, in a sense, applying the heterosexual norm to homosexuals. In other words, you license arrangements, you permit, you marry, and there’s no sex outside these license arrangements. And the fourth is total acceptance of homosexuality as a different kind of sexuality with its own norms that it itself has to discover, and if necessary police.

2. At Lambeth:

Now, at the Lambeth conference, all of these four points of view were virulently expressed. The first point was very strongly voiced, that punitive non-acceptance. I actually heard an African bishop saying “We don’t have gays in Africa, but the ones we do have, we stone.” The prevailing voice was non-punitive non-acceptance, and you know the mantra, “You love the sinner, but you hate the sin.” And that’s one of those kind of cop-out phrases that is very prevalent in this particular debate in Christianity. The liberal approach is the partial acceptance, you know it as, “We will let you operate on the same terms as us chaps.” And not to be sneered at, because it does represent a kind of development. That was routed, at Lambeth. That was the mine that went down, because the group that went there expecting some kind of compromise were decisively defeated. The total acceptance approach, well, forget it, although I think it will be the one that will actually emerge as the winner. Apart from the ugly homophobic stuff at Lambeth, there was of course, all the struggle going on with the interpretation of texts, and I alluded a little bit last night to all of that.

EPILOGUE

Let me now race through my epilogue. It seems to me that what we need to do with this whole area is what I call de-momentify sex. Take it out of its special category of complexity, this weighting that it has, this problematic, burden that Christianity has put upon it. Sex is only sex. It can go wrong, it can be glorious, it can be boring, it can sometimes become addictive, but it’s basically what Nietzsche said it was, one of the few beneficent things that Nature gives us, so why do we have to load it and pile it, pile onto it all this complexity? However, in any normal disciplined human living, we have to recognize that we can hurt one another by the way we use good things. This is a language that can hurt, so you should know your value system, you should understand where you’re coming from, and it can be addictive. And I suspect that at the base of a lot of traditional Christian anxiety about any kind of liberalizing approach towards homosexuality is a fear of raw male sexuality. I think a lot of heterosexual men would like to be given the kind of freedom that they think gay men allow themselves. And so a strong element in their condemnation of it is what Nietzsche would call resentment. Resentment is at the root of much in the Christian ethical tradition. You don’t allow yourself something because of your religious point of view, but you resent like hell the fact that some people are having it. You lie in bed at night throbbing with anxiety that somewhere someone’s having more fun than you are.

And it affects and infects the whole dialogue. Now I myself don’t know how to pick my way through this, because I know that there are aspects of the male gay sexual scene that do seem to be characterized by these absolute utopian sexual fantasies that some men have. There was a television series in Britain called “This Life,” which was about a group of young professionals living in South London, lawyers, advertising people, and there was one gay guy, because you know, you had to appeal to all classes, and it was a very successful television series. And there’s one, and they tried to be very honest about the way thirty-somethings were living in London, the fears they were having, the relationships, the drugs they were taking, and there was one seminal moment, when this handsome young man finished his dinner, and everyone’s saying how they were going to spend the evening, and he says “I’m going out for some cock.” And you see him going to Hampstead Heath, and you see him having an absolutely anonymous raw sexual encounter in the bushes. Not a word is spoken. There’s violent sex. Raw, male sexuality. And he zips himself up and goes back. He went out and he had some cock.

That is at the root of the fear of a lot of Christians about this debate, that if everything is assented to, the thing becomes explosively powerful. I myself am unsure how to tiptoe through this, and I know that most of the gay Christian ethicists I know are not simply wanting to replicate heterosexist norms, but nor are they happy with that kind of male utopian fantasy of sex on tap whenever you want it. How do you get some kind of balance in all of this? That to me, is the sexual problematic of our day.

My final word, however, is that it’s not all that important. It’s only sex. Not the end of the world. It’s just the difference between a good or a bad orgasm, or maybe too many of them, and like anything else, you can get addicted to it. So, be gentle. Be careful, but don’t overrate the thing. It’s only sex. Thank you very much.

Richard Holloway responds to questions

1. Thank you. And on the third day… I’ll try and go through these … there’s a disproportionate number of gay and I don’t know what the statistics are, but I suspect maybe even lesbian clergy, I think is an interesting fact, I don’t know the answer to it. I can make one or two guesses, the trouble is you tend to trespass into stereotyping when you make guesses about these things. But I also think that the homosexual orientation is disproportionately present in all the art forms, and I think that that has something to do with a psychology of marginalization, of inversion, I don’t know, but it undoubtedly is the case, that with this particular way of being human, there frequently goes a sensitivity to some of these areas. Social work and teaching are also, I think… I know that there are gay thrusting capitalists, but I have a kind of notion that with this particular way of being human, there is a deeper interest in the human and a sensitivity, and I suspect that’s why there is indeed an enormous disproportion there.

2. The new sexual norms thing, I mean, I’m very untidy about all this, because I don’t know. I struggle with my own sexual desires, I struggle with the tradition, and I struggle with the new things that are emerging. When, to link it with the “crap” part of my presentation, about demomentifying sex… What I think I’m reaching for here is a way that will take the kind of heavy loading out of this area, precisely so that we can maybe start thinking about ways of getting it better managed. But, I mean, I know that as a wee boy brought up in the particular culture that I was, sex was very difficult to talk about, to admit that you even had these longings. I went to confession every month and confessed to committing the sin of masturbation. No one told me it didn’t matter a damn! So the thing was momentous for me, but somewhere I learnt, in my middle age, I mean, from a doctor who said, “Ninety-eight per cent of men masturbate and two per cent are liars.” All I needed, all I needed to get, because obviously you can be compulsive about masturbation, all I needed was for someone to say, “It doesn’t matter. It happens. Think about it this way.” And it would have taken the steam and the pain out of it, and it wouldn’t have become a compulsion. And that’s really what I’m saying here.

Now I know this is dangerous stuff, I know that we can abuse one another, I know that men in particular, use sex as a kind of power thing, I know all of that, and I’m well aware of the fraught electric nature of this. But when I use a word like “demomentify,” I simply want sex to be put on a level with all the other ways that we can go wrong, and then we can maybe figure out better ways of getting it right, and I think that one of the things that we have, in fact, been discovering in recent years, because of all the various sexual misconduct things that have been going on, is that we have been identifying a proper professional ethic for people in positions of power. That seems to me to be a healthy way to go. You can abuse situations of power, you can abuse relationships or friendship. Understand that. That is the continuity within the doctrine of original sin, and that there is something about us that fouls up good things. Understand that that could be happening. Operate within a proper professional ethic. But it’s not any heavier, except because of this loading of shame. Why is it that, certainly in British newspaper culture, any public figure caught out in some kind of sexual situation, is immensely shamed by it, much more than say, by a financial situation? Can a financial corruption, which in many ways, I think is a deeper and more powerful abuse of power, it is shaming, but it doesn’t have that extra element, that x-factor.

That’s really what I’m trying to explore here, but I can’t separate my own experiences from it. So I can’t give you an absolutely straightforward answer, except that it must lie along the lines of good professional ethics. And apart from good professional ethics, I think I’m moving towards an ethic of personal variety, because people vary enormously in the way they express even their interest in sexuality. Some people have a very strong libido, some people have hardly any libido at all, and there can, incidentally, in our highly preoccupied with sex culture, there can be pressure upon people who are not very interested in it to get interested. Because they somehow feel there’s something with them if they’re not having ten high octane orgasms a week. You know, what’s wrong with me? So I think that if we can just lower the temperature on the whole subject, we can maybe begin to talk about it in a more rational way, recognizing that it is something that can go badly wrong, can be very very sternly abused.

3. Linking that to the heavy male emphasis, I was aware of that. I don’t quite know what to do about that, because I don’t have any other experience. And it’s one reason why you have a man and a woman sharing this weekend, and I hope that the balance will be provided by Mary. I mean, I know that the experiences are different. I know that there are continuities, but I can’t actually, myself, begin to enter, in a way that might help, except to know that there are discontinuities here, and I come from a tradition which saw women as being the restraining element upon male sexuality. That was the culture I was brought up in. It was pre-1963. You know what Philip Larkin said, “Sexual intercourse started in 1963, too late for me. Between ‘Lady Chatterly’s Lover’ and the Beatles’ first lp.” I mean, that’s, there was a significant seismic change in the whole attitude to sex in 1963. I was born in 1933. So I was loaded with all this other stuff, and if you read the novels of people writing in those days, it was all about men trying to get as much as they could out of women, negotiating, and women exercising a restraint upon men. They’re televising a novel in Britain at the moment, Kingsley Amis’ novel, Take a Girl Like You, and it’s about a guy trying to bed a typical fifties young woman. And it’s a very, very interesting, almost archaeological experience to watch it, because the norms have moved on. And it’s only recently that we, of my generation, have been able to talk about these things in a way that allows us to be challenged by female norms and approaches. So I do apologize for that. I mean, I stand up here as someone who is an unreconstructed male of my time, trying very hard to listen, and to be altered by what I hear. But I can’t not be who I am. But I do hear the challenge.

4. This thing about the Western experience versus the African experience. I hope it doesn’t come down to majority votes, because one of the things that used to be distinctive about Anglican, the Anglican way of doing theology, is that it was intensely contextual, that we didn’t think that a theology that suited Manhattan would be appropriate in Lagos. Because they’re very [different], except in ways that are not particularly interesting. One of the interesting things said at the Lambeth conference, when an African bishop got up and said, “Unless we condemn homosexuality, it will be evangelical suicide in my culture, because I live in a mainly Islamic culture.” And a woman bishop from Manhattan got up and said, “If you condemn homosexuality at this Lambeth conference, it will be evangelical suicide in the city of New York.” She made a perfectly valid point. Now we used to do theology contextually, and when we were debating the ordination of women, we recognized that what was a hot issue in North America, was not in Melanesia. But we implored the brethren in Melanesia to try and understand that we were responding to our cultural pressures the way they were responding. That takes enormous magnanimity and sophistication. And the thing that does worry me, and that accounts for my despondency about the Anglican Communion, I don’t see that capacity for theological magnanimity yet. It may emerge. And I know that I’m a very western figure, but I think one of the things that characterizes the western intellectual tradition is that it affirms pluraformity, it affirms multiculture, it says,” Variety is good.” Mixing, I mean, the geneticists call it hybrid vigour, when you mix things, you get better things. And I hope that patiently sticking with the debate, that will, that might slow down the naming, shaming, condemning dynamic that’s very strong in Anglicanism at the moment.

5. I think the final thing I want to say is about this balancing of the tradition with new knowledge. And the way into that for me is by a metaphor that I picked up from an English bishop, the Bishop of Ludlow, and he uses the American composer Ives as a metaphor for a way of handling precisely this tension. He says that when Ives was a young man, he was sitting in the family living room listening to a phonograph record, and he heard a brass band on the street outside, and he realized he was hearing both tunes at once. And Saxby says that, and he uses the word “liberal” but I think you can use it of a post-modern, of a contemporary person, a liberal Christian is someone who hears two tunes. Listens to the tradition, because if you are a Christian, you’re in a tradition, you’re not, as it were, living in a theological vacuum, you come from an enormous hinterland. You’re listening to that. But you’re also rooted in contemporary society. You’re reading science, philosophy, you’re going to the movies, you’re a thoroughly up-to-date person. You’re doing the two tunes. And sometimes there’s a certain amount of dissonance involved in that, and if you listen to Ives’ music, it can appear to the uninitiated to be dissonant. But there’s a kind of fidelity in it. It’s easier to become a traditionalist, or to become an absolute up-to-datist. The trick for Christians who want to affirm the tradition, is to listen to both tunes, because there are truths and wisdom in both tunes, and hold them together.

And that’s maybe one of the things that can be taken back into parish situations. Get people to listen, and the word “listen” in Biblical language is close to the word “obey.” Listening to the new things that God is saying, as Peter did on the roof at Joppa in Acts chapter 10, hearing, as it were, the correcting of the tradition, or the word that says that is no longer an appropriate way to understand this whole area of life. It was maybe right back then. It ain’t right now. Listen to the new word that’s being said.

6. How important is the church? is the final thing I want to deal with. Well, I don’t think it’s ultimately important. I think that part of the residue of imperialist Christianity is that there is a solid salvation theology in the Christian tradition, part of which is reclaimable, but part of which I think is no longer sustainable. Because it is literally believed, as it was for a very long time, that the church was in the business of literally saving people from hell and getting them into heaven. And that was what was so momentous about it, and that was the engine behind missionary expansion, because if most people were going to hell unless they heard the gospel, unless they were baptized,

then obviously there was an immense ethical imperative upon you to do something about it. I personally think that that is unethical thinking. It’s still quite strong theologically, but moving to an understanding of church that is no longer, no longer has that absolute imperative makes what you say about church much, much less compelling. Because in a sense it’s just another institution.

But my own approach to that, increasingly, is for the church to be an honest companion of human beings in their search for meaning, and a good wise way of living. Because we do have treasures, new and old, that we can share with people. And if we became, as it were, part of the journey for good people, “Come and listen to the way we live, come and hear the things that compel us, the response that we’re giving to meaning and challenge, especially as we discover it in Jesus Christ, and see if this will enrich you the way it enriches us.” It’s maybe not an absolute kind of doctrine that might scare people into the church. But there are many people out there that I think would hear that kind of wisdom approach to Christianity, and would come along and join a church without walls, and even without boundaries. I’m exploring all of this myself, have no made-up answers. One of the things that I have discovered most about my life at the end of forty years in ministry, is that I know far less than I did when I thought I knew a hell of a lot. And I speak with far less confidence. And I end up believing more and more in less and less.

Mary Hunt’s Response to Richard Holloway

Good morning, and thank you again to Richard for an insightful lecture on this the Feast of the Immaculate Conception and the twentieth anniversary of the death of John Lennon. I certainly appreciate your candour, Richard, and I am deeply appreciative of your scope, and I am most impressed by your openness, and I think you model for us the very best of what comes from institutional churches, as we try to work together on these very difficult issues.

I notice that lunch is here, so I’m going to make a brief response, and then I’ll have more time tomorrow to develop my own thoughts on some of these questions. But they flow very much, and I think congratulations to the organizers, I think the presentations flow very much in the same direction. I would like to lift up two points of agreement with Richard, and then I’d like to just outline a couple of areas, several of which have been touched upon by your remarks from the tables, but just to at least outline those, and say where we might move in discussion together.

First, I want to agree completely that sex is only sex. I think that that’s a correct insight, and that the hoopla that has accompanied issues of sexuality is really overstated. And I say that, remembering those same penance manuals to which Richard made reference. When I was studying theology, the sections in the penance manuals, this was Roman Catholic theology, the sections in the penance manuals on sexuality were kept in Latin, so that you really… the manuals themselves were by that time in English, but… My favourite section was the one on bestiality, because I really thought that the church with all of its insight would get something right, and it did. It had a little section on bestiality where it said, and you might remember this one, Richard, “Rarum fit cum tigerae.” Which means, “But rarely done with tigers.” Some of my colleagues had t-shirts made, “Rarum fit cum tigerae.” And I think that that’s about the level of analysis, and that’s why I will conclude my response by saying that perhaps the best thing the church can do is get out of this business all together.

I want to agree again that sex is only sex, but that, as has been pointed out, what Richard presented this morning, and I think what the institutional or kyriarchal churches, as I called them yesterday, have focused on has been only male sex. And I think this is a large part of the problem. And I will return to this shortly. I think what’s important, and maybe if I could suggest language for how we deal with this, the important thing would be not to discount male sex, but simply not to take it as normative. And I think what’s happened in the theological ( she said very politely), I think that the way in which male sex has been taken as normative, both in terms of how sexuality has been defined, especially in church circles, but in the world at large, is really the problem. I personally don’t have any problem with male sex. I hope men enjoy it, but I’m very clear that it’s at best half the picture. And if all of the discussion, and not just the discussion, but if all of the analysis and strategies are based on this one segment of an understanding of sexuality, I think we’re in deeper weeds than I thought.

And I think this is where, and I was delighted to hear from other women in the group this morning, that now, post, that is to say in the midst of and post-the beginning at least of the second wave of the women’s movement, we have lots to say about sexuality. We have lots of experiences to share. Some of them are similar, and some of them are quite different, and we are learning to talk about those, and I would suggest that the issue is that if sex is only sex, that’s fine. Set it aside. But the issues that I would focus on would be at least three. First, duplicity, the extent to which duplicity has been the name of the game. It’s okay as long as you don’t talk about it. Not just don’t ask, don’t tell, but don’t tell me about it because I know it’s going on. And a kind of structured duplicity that has become part of the ecclesial culture. And I say that as a Roman Catholic, that structured duplicity is very much the way in which the church handles these questions, and I think that’s an issue. If sex is only sex, fine. But duplicity is a very serious violation of Christian community in my judgement.

Second, I think the heart of the matter here is power, and I’ll return to that shortly when I talk more about women. And third, the word that I didn’t hear a lot in Richard’s presentation, and I kept waiting for, was the word relationship. And here I think, if sex is only sex, relationships are something else, and quite terribly important to me. And I’d like to talk about relationships. That’s one area. And again, I’m going to just lay these out and we can talk about them as the weekend progresses.

I’d like to go back to those four approaches that Richard laid out as well, because I think that he’s right. I know that they’re not original to Richard, but I think they’re right. I would add a fifth, because I think that part of the problem is that there’s lots more going on. And the fifth would be this: I would take the tolerance that the total acceptance as a given. In other words, I would move immediately to that fourth position and say that where this is going is not simply total acceptance on the basis of homosexuality being different, but now with bisexuality/transgendered questions, what Virginia Ramy Mollenkott is talking about in her new book, Omnigender, I think we need to be talking beyond mere, beyond total acceptance to a new norm for everybody. It’s not just with new norms for homosexual people and some norms for heterosexual people that have been there a long time, but part of the logic of sex is that it’s self-involving, and part of the resistance to talking about sexuality in new terms is because if I say it’s okay for you to be bisexual, then I have to say there’s something human about being bisexual which might include me. Or if my mother or my father, or your mother or your father had to say it was okay for you to be a gay or lesbian person, at some deep level he or she had to say that it would be okay for him or her to be gay or lesbian. And I think that logic of what Deedee Evans called about God the logic of self-involvement, that the logic of self-involvement in sexuality is really critical. And part of this mania around issues of homosexuality, I think comes from people who implicitly understand that, but deny, deny, deny.

And that, I think, is a very important thing. If I say it is human to be bisexual, or it is human to be, and I frankly have never understood myself as bisexual, I was bicoastal in the sense that I lived in … [piece missing] … and I think that’s very very common in terms of homosexuality as well, that the resistance comes from not being able to admit the possibility that that which is so deeply human for someone else can be deeply human for me as well. I think that’s a very key question.

Which is why it becomes important to talk in very specific terms. And here I’d like to lay out a couple of areas where I think we need to talk. One is this question of a male utopian sexual vision. I think that that comment, and I know where Richard was coming from when he made it, but I think it’s very helpful because the male utopian vision that the media would put out in that series, which I think now is coming to the States at least, of so-called raw sex in the bushes, needs at least to be critiqued from a variety of points of view, starting with women’s experience. Because I think it is not when women begin to talk about sexuality, it’s not that we’re looking for a utopian vision. We are looking at the everyday experiences of most women in terms of issues of violence, issues of power, and issues of pleasure.

And I engaged in a project, the book for which is coming out in February (’01), it’s called Good Sex. Great title, huh? Good Sex: Feminist Perspectives from the World’s Religions. And what we did was, we got together a group of a dozen women, from eight countries and six religious traditions, Jewish, Christian, Muslim, etc., and we came together as a group of women scholars and activists, and we talked about what good sex would be like from feminist perspectives around the world. And I will leave you to read the book for the conclusions, but I will summarize it by saying that we, I think it’s fair to say, we shifted the focus from the bedroom to the boardroom. We shifted the focus from the bedroom to the boardroom. Now there were, there are essays in this book and there was discussion among us, and we had a magnificent, two magnificent meetings, one in Philadelphia and one in Amsterdam, went right to the heart of the matter in the Netherlands. And what we talked about was if women were to bring the richness from our own religious traditions to talk about what good sex is, what we would say. Of course the Catholic chapter’s very thin, but …

In any case, we were participants. What we talked about were all the range of issues, from the questions of taboos, to the question of delight and pleasure. I personally wrote on the human right, sex as a human right, imagine if the UN were dealing with good sex as a human right. The human right to good sex is what I actually have written about, and I believe strongly that this kind of approach, which sees sexuality not in terms simply of bedroom issues, but of boardroom issues, is a way to move this conversation with a variety of cultures and religious traditions involved. Because we’re looking at issues of safety, issues of economics, the trafficking of women, issues of prostitution. We’re looking at questions of HIV/AIDS, we’re looking at the right to pleasure and who defines and describes pleasure, we’re looking at the way in which various sexual practices work. So this approach, I think, is one example, and I don’t want to belabour it, but it’s one example of how, as women begin to enter this conversation, ecumenically, internationally, and from an activist perspective, the focus shifts, from these, what I would call frankly bedroom issues, or what Dan Maguire calls the “pelvic zone,” to the boardroom, or what I would see as the free enterprise zone, and all the critique in post-industrialism capitalism that needs to be brought to that.

So I bring that to your attention, because I think that women’s experience is very different. Another way in which it’s very different is that the problem of shame, I think, simply doesn’t exist for women in the same way. What does exist is the problem of violence. And to begin to relativize these questions and to see that the female body, especially as we are engaged in things like childbirth, and lesbian sexuality, that the female body questions are really not so much questions of shame as they are questions of power. How will one have the right, the human right, to good sex. And I think it’s very important to bring that up in this context, and see it as part of the deconstruction of this kyriarchal institution that I’ve described as our culture.

Last night I used the term “kyriarchy” from Elizabeth Schussler Fiorenza, and I was really contrasting it with the word “patriarchy,” patriarchy of course, being the Latin word that describes father-right, which Richard referred to, the way in which male privilege works. But kyriarchy, coming from the Greek, some of you are old enough to remember the “Kyrie Eleison” and well, maybe you do it in this church. But the kyriarchal or structures of lordship over against, play themselves out here, so that if I thought of the sexual fantasy, or even the utopia of a woman who was a prostitute, it would not be a quick fling in the bushes. But it would be the notion of having a roof over her head, and a bed in which to have sexual relations, and to choose the person with whom she will have sexual relationships, and that she will be safe, both in terms of the sexual practice, and that she’ll have medical care if she requires it related to her sexuality, or just medical care at all. And so, when I begin to think about that, sexuality from that perspective, it helps me to begin to move, I think, into a new conversation that I described in a thumbnail, from the bedroom to the boardroom.

Finally, what’s the task of the church in this? In all honesty, I am fairly persuaded that maybe the best thing the church can do is get out of the sex business entirely for a while, and learn from the culture. And I don’t mean that in a cheap way, because I really do, as I said last night, believe in the renewable moral energy of religions. But I’m not persuaded, on this topic, that we have much more, that the churches as institutions, have much more to say. And in fact, they have become so much a part of the problem instead of being part of the solution, that I wonder if we might not put a moratorium for a while on the church as a resource for sexuality education, or for morality education. And again, how that would play itself out in the Anglican Communion I would be the last to say. But certainly in the Roman Catholic Church that has gotten it so wrong on masturbation, birth control, abortion, homosexuality… what makes me think staying with hope that that institution’s going to have something to say. And as one of our good Catholic sages, Teresa Cainwun said, “It’s really unfair to ask te church for something it’s unconstitutionally unable to provide. You only become frustrated.” And I was thinking about the analogy to domestic violence, that people who work in domestic violence work, have realized that the churches are not experts on this question. And the best thing that most ministers can do is refer people who come to them with questions of domestic violence to people who are experts, who exist in the culture and who are doing magnificent work unfettered by many of the problems the churches have around these questions.

And I wonder if it isn’t time to do the same thing on some of the questions of sexuality, to say that there are people who are specialists in these areas in terms of the biological and sexological sciences. There are people who are better equipped to understand especially the experiences of young people today. And I think it might be a time to really ask the question a different way. Let’s say the churches leave sex alone for a while, and we focus instead on issues of duplicity, internal to our own institutions. We focus on issues of power as they would play themselves out in terms of our values of love and justice, and our attempts to be a discipleship of equals. And we reflect on what it is that we want when we say we want to live in right relation with ourselves, with one another, and with the Divine. And then perhaps the best thing we could do is pray for forgiveness for what the church has done, and then hope for something better by working with those who are really experts in the field.