Mary Hunt Homily at the Church of the Holy Trinity

Baruch 5:1-9; Luke 1:68-79; Philippians 1:3-11; Luke 3:7-18

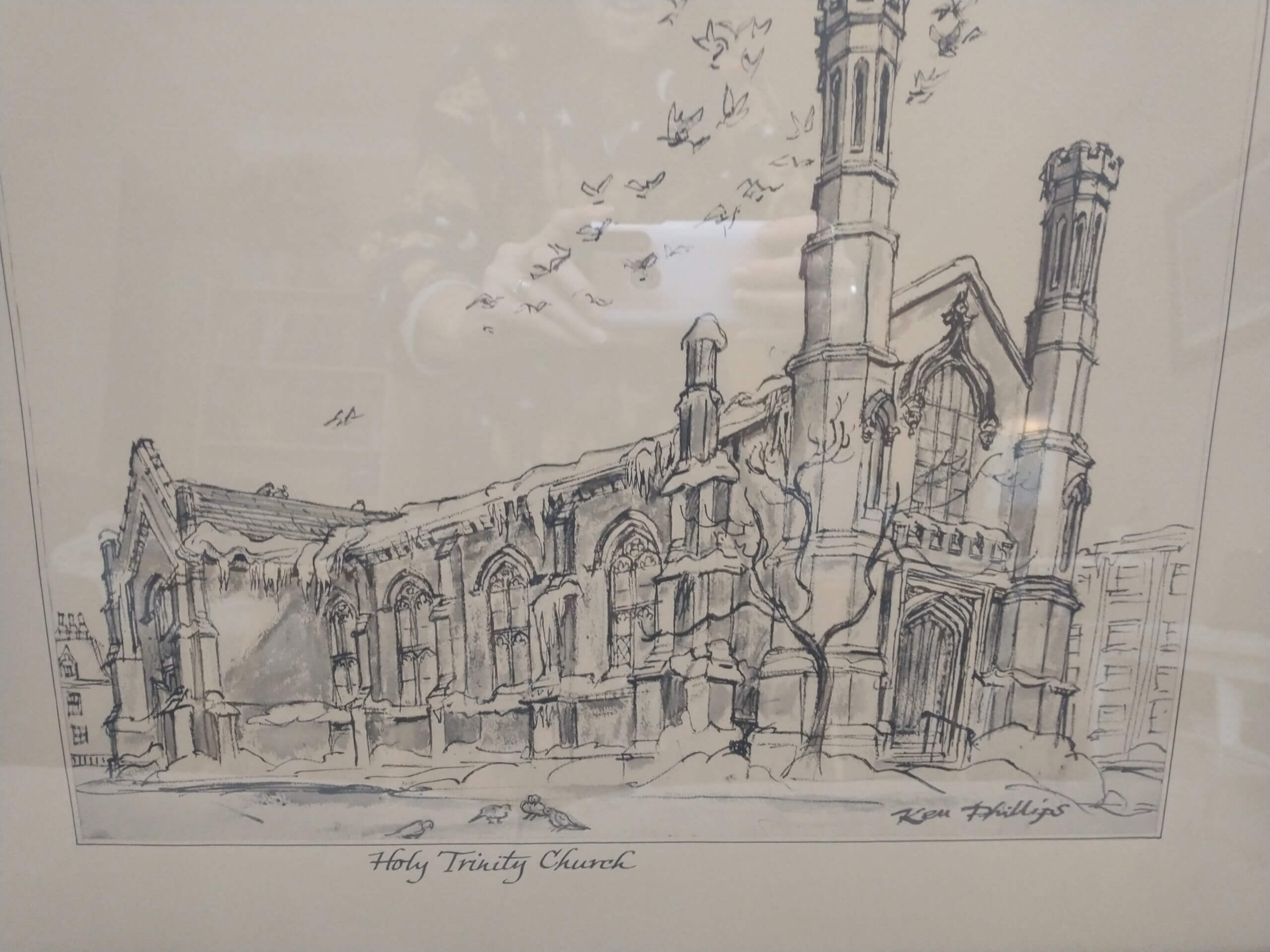

Good morning and peace to you this beautiful winter day! I am deeply indebted to this church community for inviting me to participate in the weekend’s profound and enjoyable conference, “Loving Justice: Celebrating Queer Holiness.” I am delighted to be in a church that was built on sacred ground and funded by a woman, Mary Lambert Swale, and that is pastored by a woman in the same generous tradition. Thanks to Sally Boyles for extending me the courtesy of this pulpit.

I join you for the Eucharist this morning in the fullness of Roman and Anglican communion of which some of our church officials only dream. May they follow our lead and one day know our joy at being together at this table. Those of us who have been together throughout the conference can report with pleasure that we have been challenged to rethink basic presuppositions, that we have enjoyed one another’s company both in prayer and feasting, and that we have been encouraged by the strong presence of Archbishop Richard Holloway from Scotland who proves that there are institutional church people of pastoral and personal sensitivity. Now we are charged up, enlivened by our own words, to be a church that is called to go into the 21st century making queer justice and deepening our queer holiness. We did not strategize and critiques churches “out there,” but spoke of the whole church, ourselves included, as one body just as we celebrate this morning’s liturgy as one. Anything else is simply unworthy of our tradition.

This morning I join my voice to those who engage in the Dangerous Practice, as the title of that wonderful collection of queer sermons from this church would have it. I am indebted to Susie Henderson, Jennifer Henry, Jim Ferry and the rest who have paved the way. I pray this morning that my words might be a faint echo of the powerful, courageous preaching here over the years when such was not as easy as it is today. I want to affirm with you this morning my conviction that what we have been about this weekend, indeed what you are committed to and have suffered for as a parish community, and what the whole church gets from you, whether they want it or not, is that you have taken seriously the fact “that your love may overflow.” I believe that as gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people and our supportive friends committed to justice and holiness, our task is to affirm the overflowing bounty of love that at a moment dared not speak its name, but now dares not keep its mouth shut!

By that I do not mean a stereotypic flaunting of what was previously prohibited, but a healthy, indeed a holy articulation of the blessing we have received. It is to live at a time, when, with our help and through our pain, our love, all of it and in its myriad forms, is seen as part of the goodness of creation. To miss this is to miss a powerful resource for dealing with so many forms of racial, economic, sexual and other forms of injustice that form the global context in which we find ourselves today.

I take my inspiration for this morning’s sermon from what for a feminist theologian is an unlikely source, namely, the writings of Paul. I think Paul has received and deserved a fairly dubious reputation with regard to his pronouncements on women. But in today’s Epistle, his Letter to the Philippians, Chapter 1 verses 3-11, I had the feeling he got it right. I sensed that he was addressing himself as much to us as to his own community.

Paul’s mode in this letter, as in most of his letters, was prayerful and grateful. He waxes poetic about how thankful he is to God every time he “remembers” the community. But what is extraordinary in the text is the number of times he writes that all of them, without distinction, are included in virtually every one of his pronouncements. “It is right for me to think this way about all of you, because you hold me in your heart, for all of you share in God’s grace with me…” “And this is my prayer, that your love may overflow more and more with knowledge and full insight to help to you determine what is best…” Such knowledge is the work of the Spirit in the world, an odd, unprovable statement that we affirm as we go about the works of justice and holiness seeking the fruits of Her Wisdom, Sophia.

Reading this Pauline passage through what I can only call a queer hermeneutic or a lesbigaytrans lens of interpretation, it is hard to understand why we have had these struggles in our churches for the past thirty years, and why in all probability we will have them for thirty years to come. The text seems so simple, so crystal clear, and so unambiguous in its inclusion of each and every one. What is the problem?

This would be my question to the good people of the Lambeth Conference and those who oppose full inclusion, including ordination and marriage: to whom do you think Paul was addressing his words? What part of “all” don’t you understand? What aspect of love have you missed such that you can not see it when it is right in front of your eyes, I might query queerly. If you read this text as I do, that it expresses the love of one Christian for the whole community, all of them, and that it expresses a certain awe at the quantity and quality of love that Paul experienced, then it seems logical to conclude that Christian communities would welcome in an ongoing way the range and depth of love that appears in their midst. I admit that religion is not logical, but we can be. It seems exegetically sound and pastorally prudent to put the shoe on the other foot and ask those who would discriminate to make the case why they think they need to correct

Paul’s mistaken inclusion when it comes to us. This insight into love came to me from two quite different sources—U.S. Mercy Sister Theresa Kane, and former Lutheran Bishop of Stockholm, biblical scholar Krister Stendahl. Love always comes in very particular packages, and I am deeply grateful for these two. Many years ago, when the Conference for Catholic Lesbians began, we met at the Kirkridge Conference Center in Pennsylvania, known to some of you (Jim Ferry at least) as a haven on a hill for progressives, a place whose motto is “picket and pray.”

There we were, more than a hundred Catholic lesbians in the early 1980’s, gathered for the first time to think about the seemingly incompatible reality of our being lesbians and Catholics. What was expected to be a weekend conference turned into an organization with a newsletter and a website; the moral of story is be careful when you have a good conference!

At one session we were privileged to listen to Sister Theresa Kane. There was a lot of pain in the room, but there was expectation as well. Sister Theresa Kane, a Mercy nun from Yonkers, N.Y., was the president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, in short, the ranking US nun if there is such a thing. You may recall that she was the one charged with greeting the Pope on his first visit to U.S. soil in 1979, something she did with dignity and grace. However, she took the occasion to remind him gently that full ministry for Roman Catholic women was still a thing of the future. He was not amused, to put it mildly. The press captured his displeasure that eventuated in deep suspicion of American Catholic feminism, but that is a story for another day. Theresa Kane was and is a heroine to many of us at the conference. There she was, putting herself on the line again by showing up as a speaker at the Conference for Catholic Lesbians. Of course everyone wanted to know if she were a lesbian, so when she got ready to finish her marvelous lecture women were hanging on her every word. I was moderating, and I, too, was on the edge of my chair, not sure what was to come and what I was supposed to do. Finally, she turned to me and said, “Mary, do I have time to discuss my own experience on these issues?” I responded like any good moderator, “We don’t have time for you not to!”

Then in very simple, clear language she described how she had gone to her first conference for gay and lesbian people sponsored by New Ways Ministry, a Catholic support organization for lesbian and gay Catholics, their families and friends. She said that as a nun, her own sexual preference had been obscured from her. In a sense, celibacy meant you did not have to think about it. She continued, “I went to that conference and I saw gay and lesbian people who loved one another. I saw love there and I knew as a Christian that I had to recognize it.” As you might imagine, women were crying with joy that this marvelous woman, who was already in enough hot water, had the ability to see love and know what it was despite the fact that as a Catholic nun in a sexist church her own sexuality, whatever it may be, had been kept from her. I can report that we did not get the answer we were looking for about Theresa Kane’s sexuality, which, frankly, to this day I consider no one’s business but her own. But we did get a dose of the Gospel as I had never heard it preached before. In a way we were quite naïve then, but I believe that anyone, even a Martian, coming into a community like this, or into the women’s base community to which I belong, or into any number of Christian communities where glbt love is taken seriously would have the same reaction. To miss love as it overflows before one’s eyes in the person of same-sex lovers, to deny or denounce the love of same-sex people for their children as the Vatican has done recently, is to blaspheme the very texts we hold dear.

The other source of my conviction on this matter of love overflowing comes from Krister Stendahl, longtime professor and dean of Harvard Divinity School, and later Lutheran Bishop of Stockholm in his native Sweden. Krister wrote relatively little during his academic career, but taught quite a lot, rather the way I assume Jesus behaved who never set a word on paper as far as I know, never sent an e-mail nor called anyone on a cell phone, but taught quite a lot nonetheless. I have always carried with me Krister Stendahl’s words from his book entitled Jesus Among Jews and Gentiles in which he claimed that the heart of the Christian message is the ultimate triumph of love even over integrity. By that he does not mean that integrity goes out the window. Rather, he means to underscore dramatically just how important love really is, so important that one might have to give up a deeply held position, a well steeped prejudice, a tradition-bound dimension of one’s faith in order for love to triumph.

This is hard for many people in the face of a son who comes home and says he’s gay, a daughter who announces that her lover is pregnant, a man who decides he really wants to be a woman, a woman who needs to go beyond heterosexuality. But for people who profess the Christian faith I can not find any evidence to suggest we have any choice but to love. The problem of course is that we just do not know where it will end. Just when we get comfortable with gay and lesbian people, along come our bisexual friends to upset the apple cart. Just when we have incorporated a little of their reality into our common life our transgender friends come along and force us to re-examine every category we have ever held dear. Now that we can not tell all the genders without a scorecard, now more than ever we need Paul’s advice to let your love overflow “more and more with knowledge and full insight.” It is no easy task, as we have learned this weekend, no easy task ever.

Happily, it does not end. That is the grace of being part of an historical tradition. We have the assurance that successive generations will come along with new knowledge and new insights, and love will still undoubtedly be the best remedy for their uncertainty, too. While Paul could never have predicted today’s sexual diversity, neither can we predict what is ahead. What we can predict with fair accuracy is that gatherings like these, around the table without distinction and with a warm invitation to eat and drink in memory of her, and in memory of him, and one day in memory of us, are the proof that love overflows when we let it. It is up to us, because the Spirit has already done her part, providing Theresa Kane, and Krister Stendahl, and each of us as a font of this overflowing love. Let’s enjoy it.

Amen, Blessed Be, Let it be so.

Loving Justice Conference Plenary Notes

Church of the Holy Trinity, December 7-9, 2000, Toronto, Ontario

For individual use, reprinting requires author’s permission