Sherman Hesselgrave

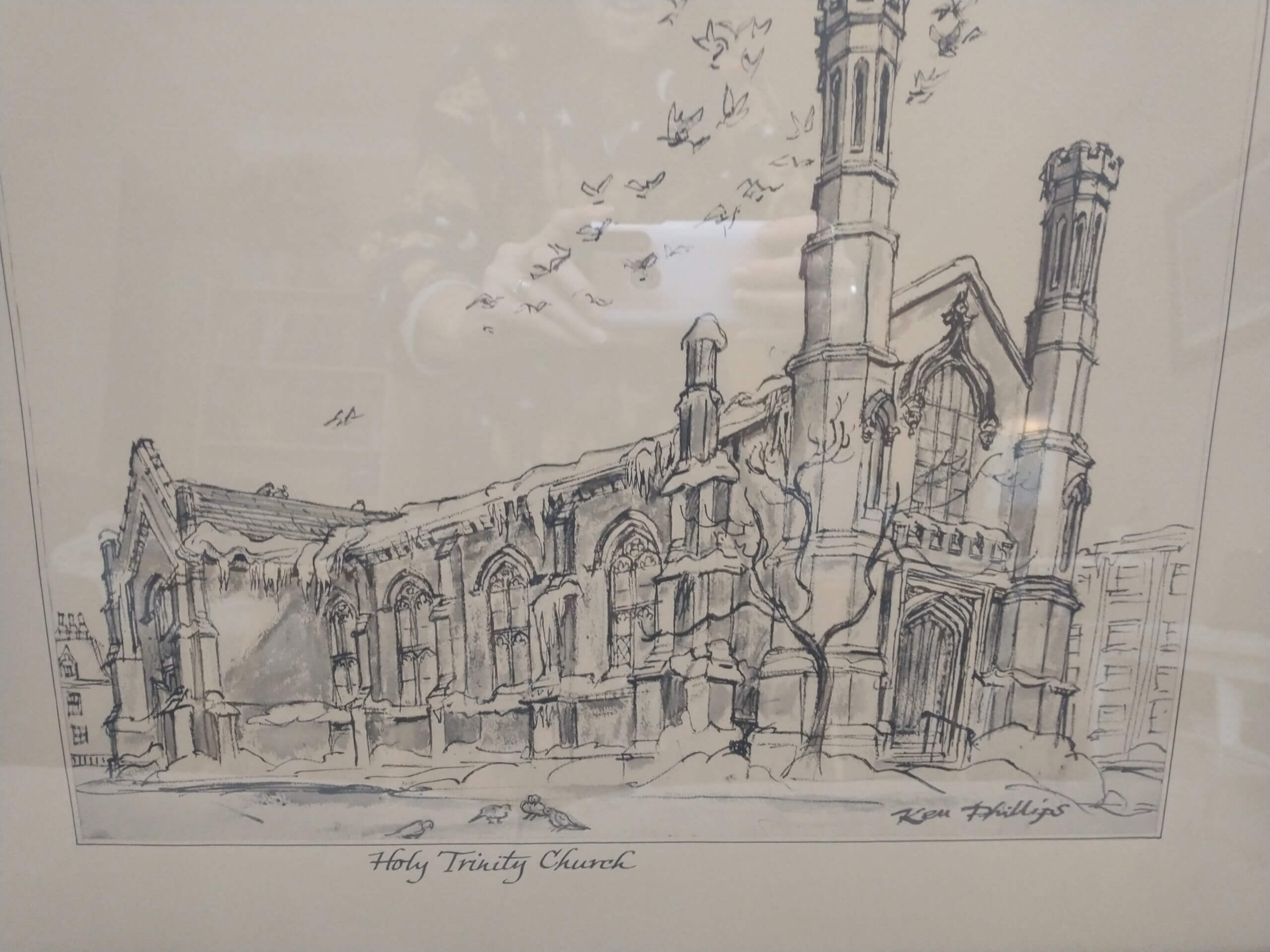

Church of the Holy Trinity, Toronto

17 March 2013

Isaiah 43 Psalm 126 Philippians 3:4b-14 John 12:1-8

Stop dwelling on days gone by and brooding over events long past.

I am about to do a new thing;

at this very moment it is unfurling from the bud—

can you not see it? —Isaiah 43

Thornton Wilder wrote that the “whole purport of literature…is the notation of the heart.” [The Bridge of San Luis Rey, p.16]

In seminary, I took a course entitled Evil and Recovery: A Christian Perspective on Shakespeare.

One of the most dramatic themes in literature, and well represented in the canon of this great

documentarian of the human heart, is the theme of renewal. And one of the most memorable

insights I took away from that class was a deeper understanding of ‘kindness.’ Whether one is

unpacking the text of As You Like It, King Lear, or The Tempest, what often makes renewal

possible for Shakespeare is the transformative nature of kindness, the recognition that we are all

of one kind. Kind-ness. Whether in the socially stratified world of Elizabeth England, or in our

own, where the chasm between rich and poor expands daily—kindness is the practice of the

biblical command to “love one’s neighbour as oneself.”

By becoming human like us—literally sharing our kind-ness—Jesus, through his actions,

storytelling, and faithfulness, lived the self-sacrificial love that brings about the healing of

creation. Shortly before his death, in the context of the Last Supper/First Eucharist, Jesus gave his

disciples a very easy-to-remember commandment: “Love one another as I have loved you.” He

expected them to figure out that by doing so, they would become partners in God’s plan of

bringing about God’s reign.

We encounter that kind of selfless love in the person of Mary of Bethany. The dinner

given in Jesus’ honour bears some similarities to the meal in the upper room where Jesus will wash

the disciples’ feet a few days later. Mary’s generosity is scandalous to some in Jesus’ entourage; to

them it is extravagantly wasteful to spend the equivalent of a year’s wages for this embarrassing

and sensuous display that would normally be performed on the body of a person after death;

certainly, not at a dinner party.

There are two observations about the Bethany scene to which I would draw attention:

First, a closer look at the concept of ‘generosity.’ Though the word itself does not appear, Mary’s

generosity is unequivocal. It is worth noting that our English word, ‘generosity,’ is related to the

Greek and Latin verbs meaning ‘to give birth to.’ I would even go so far as to posit that generosity

is one of the mechanisms God has provided to bring about a “new thing” when a “new thing” is

needed. Anyone who has committed or been the recipient of a random act of kindness knows the

power that generosity can unleash, the hope it can create, the healing it can catalyze. Never

resist a generous impulse is a worthy personal motto.

The second is the inclusion of the detail that “the house was filled with the fragrance of

the ointment.” Recall that, in the previous chapter, when Jesus arrived after Lazarus had been

dead four days, Mary’s sister Martha warned that there would be a stench if the tomb were

opened. Now the fragrance that fills the house is a fragrance more powerful than the stench of

death, perhaps it is even a sign that Jesus’ resurrection will remove the fear of death forever.

Mary’s generosity has transformed the life of this entire household—her generosity is literally in

the air. At the moment, they may not realize the extent of that transformation, but, as

philosophers have noted: life is lived forwards, but understood backwards.

Grace—the generosity of God—is always transformative. In today’s Isaiah reading, the

prophet reminds his audience that God’s grace saved them when they were delivered from

slavery in Egypt, but God does not want them to become fixated on what happened in the past to

the exclusion of the new thing God is doing at this moment. The situation seems bleak on the

ground. Israel is still in captivity in Babylon. Something life-giving—the defeat of Babylon—is

about to bud, but the attention of God’s people is elsewhere. God promises streams in the desert,

but their eyes are on idols. The Second Commandment warns of the danger of placing other

gods before Yahweh. Every idol demands human sacrifice, whether it is Moloch, who required

the sacrifice of children; Aryan Purity, which resulted in the sacrifice of millions who were

deemed not to qualify; Economic Oligarchy, which was called out by the Occupy Wall Street

movement; or Chemical Dependency, which has destroyed families and dragged millions to an

early grave. Whatever draws us away from God draws us away from the deliverance, the “new

thing” God has in store for us.

Sometimes we avoid grace because we know it will bring about our transformation, and

we fear change. The comfort of what is familiar trumps the leap of faith we know we should take,

the new thing that will bring new life, but will also move us out of our comfort zone. How many

times have we heard of congregations who say they want to grow, but when new people try to

stake a claim in the community, offering their gifts, which might include doing something a

different way, their ventures are foreclosed because they upset the community’s equilibrium or

threaten domains of power? To walk by faith, and not by sight, means there will be times we

simply can’t see for certain what is around the corner, but we have to step off the curb. We

HAVE to move out of our comfort zones.

Despite Isaiah’s exhortation to stop brooding over events long past, the past is always

present, in the sense that, everywhere we go, we carry the results of every choice we ever made,

and, as T. S. Eliot put it, “every moment is a new and shocking/Valuation of all we have been.”

[Four Quartets, “East Coker,” II]

When the burden of stingy or poor choices overwhelms us, however, God’s grace is capable of

lifting that burden from our hearts and steadying us on a new path. The second verse of today’s

gradual hymn, Holy Woman, Graceful Giver, states this reality in terms of today’s gospel:

Like the vessel [i.e., the ointment jar], we are broken;

Like the ointment, we are token

Of God’s loving unto death;

Like the woman, we are serving;

Like the scolders, ill deserving

Such a rich, forgiving faith. [Words by Susan Palo Cherwien]

Sometimes the “new thing” that God has to offer is a fresh perception of something that

has long been taken for granted. There is a famous optical illusion, called the duck-rabbit

illusion. You have probably seen it. A simple black-and-white drawing that can be perceived

either as the head of a duck or the head of a rabbit.

The image is static; what changes is the way our brains manipulate the visualized information to

interpret it. The night sky looked pretty much the same the before the Copernican revolution as it

did the day after the Aha! moment. But the scientific community would never see it the same

way again. Of course, the Church would take somewhat longer before it could come around. It

is understandable that the Church would be slow to adopt a new way of thinking that overturned

centuries of theological reasoning and assumptions. But, in the end, it had to accommodate the

new perception. As a nun I knew long ago once told me, “The Church changes very slowly—

one funeral at a time.” Sometimes the old ways of seeing simply have to die out before the

perception of God’s vision can come into focus.

God. Promises. Renewal. The “new things” we thirst for—the streams in our desert—flow

from the practice of giving our whole selves in radical trust to God and by faithfully living the

generosity modeled by Jesus, by Mary of Bethany, by the little boy with the five loaves and two

fish, by the father of the Prodigal Child, and by countless saints through the centuries, who

accepted God’s invitation to share in the abundant life that Christ offers all who love God with

heart, soul and mind, and their neighbours as themselves.