Acts 2:42-47 Psalm 23 1 Peter2:19-25 John 10:1-10

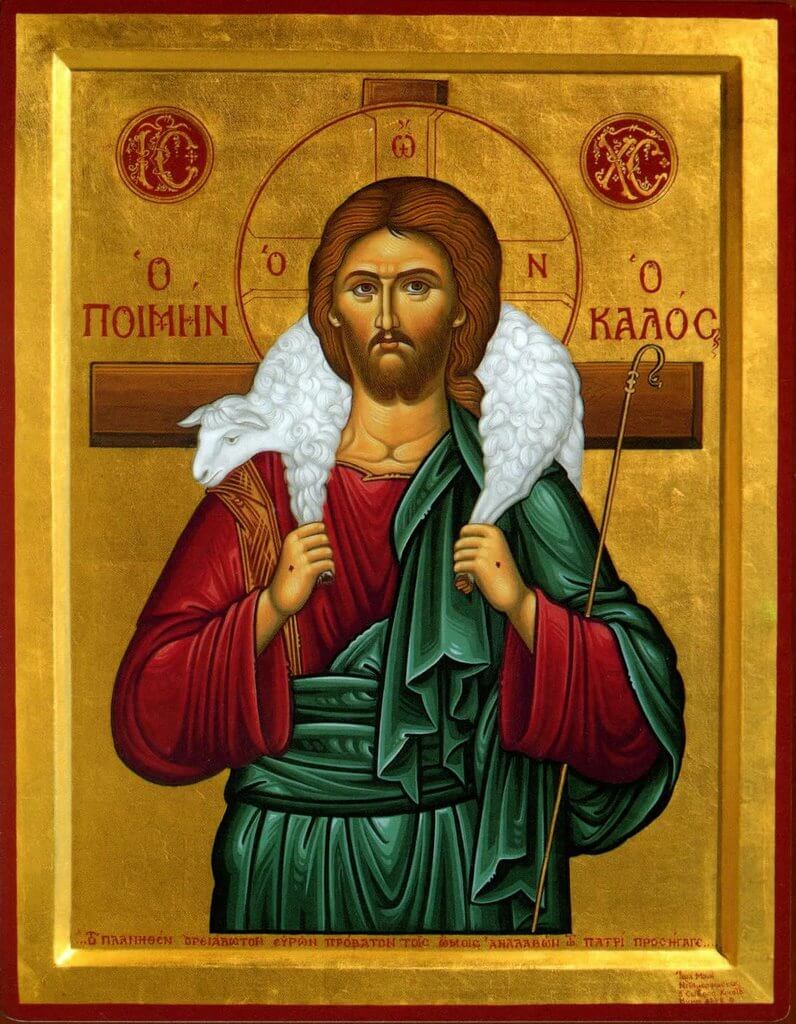

This Sunday in the Easter season has long been nicknamed Good Shepherd Sunday, as you may have gathered from the gospel reading and the 23rd Psalm. There is a long tradition of portraying Jesus as the Good Shepherd; there are numerous depictions on the walls of the catacombs of a shepherd carrying a sheep on his shoulders. The Gospel of Matthew records that, “when Jesus saw the crowds, he had compassion for them because they were troubled and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.” [9:36] What caught my attention this time around, though, was the epistle reading, and its focus on pain and suffering. I was surprised at the number of memories it evoked. In my youth, when I worked as a music librarian, I had a Roman Catholic colleague, who was one of fifteen children. One of the things she heard regularly as a child, when one of them would whine or complain, was, “Offer it up. Our Lord hung on the cross for three hours.”

A tradition so fixated on the crucified Christ—crucifixated, if you will (I’m claiming the coinage, since ‘crucifixated’ produces no Google results)—was bound to produce aberrations like self-flagellation as a spiritual practice and gruesome acts of penance, to keep the theme alive.

In 1846, one year before the founding of Holy Trinity, the first surgical anesthesia was used. Most people would have considered it a miraculous and welcome discovery, but its acceptance was slowed, in part, by clergymen, who “deplored its use to reduce pain during childbirth as a frustration of the Almighty’s designs.” [Atul Gawande, The New Yorker, July 29, 2013] What designs were those, one might ask, and the answer can be traced back to the narrative of the eviction from the Garden of Eden in Genesis [3:16,17]:

To the woman [God] said,

“I will make your pregnancy very painful;

in pain you will bear children….”

To the man [God] said, “…cursed is the fertile land because of you;

in pain you will eat from it every day of your life.”

Our tradition has a long and complex relationship with pain and suffering.

C. S. Lewis wrote that the problem of pain, in its simplest form, is this: “If God were good, [God] would make His creatures perfectly happy, and if God were almighty, [God] would be able to do what He wished. But the creatures are not happy. Therefore God lacks either goodness, or power, or both.” Rabbi Kushner, in When Bad Things Happen to Good People, used a similar approach in his analysis of the story of Job. An extended look at theodicy—the answer to the question of why God permits evil—is beyond our scope today, but I will say that I have known more than a few people who were unable to believe in a God who would permit the kind of evil that has taken place throughout history.

Life includes pain and suffering: We experience the loss of our parents. We get cancer. We get old and have ailments. A child is killed in a car crash, or becomes paraplegic. A loved one is raped or murdered. Our job is made redundant. Our pension is lost through corporate fraud. We experience betrayal. The poet, playwright, and diplomat, Paul Claudel, in acknowledging that pain and suffering are part of the human experience, took this view: “Jesus did not come to explain away suffering or remove it. He came to fill it with his presence.” In other words, God sits with us in our depression. Accompanies us through the valley of the shadow. Holds our hand in our moments of fear.

The first two chapters in Dorothee Soelle’s book, Suffering, are entitled “A Critique of Christian Masochism” and “A Critique of Post-Christian Apathy.” The book explores two questions: “What are the causes of suffering, and how can these conditions be eliminated?” and “ What is the meaning of suffering and under what conditions can it make us more human?” She relates an episode in the life of Simone Weil, the French philosopher, mystic, and political activist. As a way of better understanding the working class, Weil had spent a year working as a labourer in a factory. In this letter from about May, 1942 (the year before she died at the age of 34), she wrote:

After my year in the factory, before going back to teaching, I had been taken by my parents to Portugal, and while there I left them to go alone to a little village. I was, as it were, in pieces, soul and body. That contact with affliction had killed my youth….

In this state of mind then, and in a wretched condition physically, I entered the little Portuguese village, which, alas, was very wretched too, on the very day of the festival of its patron saint. I was alone. It was the evening and there was a full moon over the sea. The wives of the fishermen were, in procession, making a tour of all the ships, carrying candles and singing what must certainly be very ancient hymns of heart-rending sadness. Nothing can give any idea of it…. There the conviction was suddenly borne in upon me that Christianity is pre-eminently the religion of slaves, that slaves cannot help belonging to it, and I among others.

Soelle comments: “[Christianity] is the religion of the oppressed, of those marked by affliction. It concerns itself with their needs. People are pronounced blessed not because of their achievements or their behaviour, but with regard to their needs. Blessed are the poor, the suffering, the persecuted, the hungry.”

We are all too aware of the pain and suffering the church as an institution has inflicted over the millennia. Christianity may be the religion of the oppressed, but the church has often been an institution of vast human power, and as such, vulnerable to all the myriad abuses that powerful humans can conceive, no matter how well-intentioned or rationalized. And, while apologies have been issued—sometimes hundreds of years after the offence—,and more apologies are still to come, there is embedded in Jesus’ message a vision of God’s reign. If we believe it is real for us, and if we act as we believe, then, in the midst of a screwed-up world, there will, like Swiss cheese, be little pockets where the reign of God is breaking out, and it will make a difference to everyone who is touched by it. Living in a world where so many things are beyond our control, I close with a prayer that is offered by millions of people every day:

God grant me the

Serenity to accept the things I cannot change

Courage to change the things I can

and Wisdom to know the difference.