I won’t spend time this morning on the dispute between Jesus and the Pharisees about the question of of healing someone on the sabbath. Instead I will focus on the question of healing itself, prompted by the story of a healing in today’s gospel reading. I’ll just offer a few reflections and raise a few questions about healing, health and wholeness.

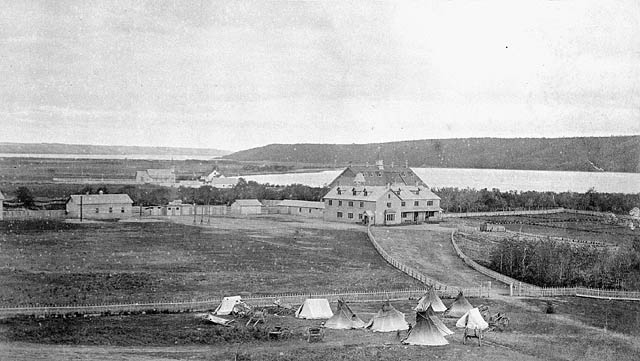

There has been a lot in the news lately about the question of healing with reference to the shocking treatment of indigenous children in residential schools and its grim aftermath. Clearly, there is a huge need for healing in this instance – healing, forgiveness and reconciliation. The pope’s visit was probably a positive step in this respect but whatever we think about the pope’s visit, (and obviously there was divided opinion) we have to acknowledge our own complicity as Anglicans who ran a lot of residential schools and members of a society that established them in the first place And it’s not just ancient history. The practice has reached right into our own time. Last night I watched the CBC Fifth Estate program on the discovery of unmarked graves of hundreds of indigenous children who had been in residential schools. For family and other community members it documented what they knew and the pain and anger they expressed was a hundred percent legitimate.I’ll come back to that later. But evidence of the damage done in residential schools is there for all of us to see on the streets of Toronto. The least WE can do by way of healing is to act on the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation report and that action has to be part of a continuing process….

Well, in a quite different context, the very idea of healing can be problematic. I knew a psychiatrist who, years ago, was committed to healing homosexuals – healing them by making them hetero For us at HT it’s a shocking idea but we know there are still places today where such “healing” practices are promoted. Marilyn Dolmage could give other examples of problematic ideas of healing but I will offer just one example (that Marilyn is familiar with). Lee has a brother, Norm, who has cerebral palsy. Norm’s list of achievements is quite stunning. I remember sitting on the Convocation platform at the time of Norm’s graduation from York. A citation was read listing all the things Norm had done to earn the highest award given in his graduating year. A person sitting next to me said that’s truly amazing, just imagine what he could have done if he didn’t have cerebral palsy. I reported this to Norm who is a very sociable person and he laughed saying if he didn’t have cerebral palsy he would probably have spent all his time partying, and boozing it up with friends. At one point when Norm was younger he was offered something by way of a “cure”, a surgical procedure which might reduce if not eliminate his palsy. Norm’s response: I don’t need any cure, any healing– this is who I am. I don’t need to be cured. We have to be very careful not to assume that certain people need to be cured of what we may think of as a disability.

This raises the question of what we might call wholeness, or perhaps, what we might call “human.” How do we respond, for instance, to a person with dementia? It’s going to be, increasingly, an important question in our society. Such a person is still a human being with a name and a history. In the past, Lee and I regularly visited a friend with Parkinson’s involving severe dementia. He had been a distinguished and important medical scientist, and while his cognitive capacity was now severely limited, it was quite natural for us to continue relating to him as a friend, a person we had known for a long time, whom we cared about, whom we loved, and he responded to that recognition, perhaps not in the way he would have in the past but still with a smile of recognition, a sign of a life respected , a life affirmed. Not a moment of healing exactly, but nonetheless, a moment of communication or communion between whole persons

You probably won’t be surprised to know that I spend a certain amount of time reflecting on aging. Are aging persons still whole human beings who deserve to be treated as such? Recently I was re-reading T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. At one point in the narration a stranger turns up and in the course of conversation says “Let ,me disclose the gifts reserved for age to set a crown upon your lifetime’s effort. First, the cold friction of expiring sense, Without enchantment, offering no promise but bitter tastelessness of shadow fruit as body and soul begin to fall asunder.” A pretty bleak picture painted by this stranger . It doesn’t correspond to my own experience, ( although the expiring sense of hearing certainly doesn’t hold any enchantment for me!). I think about the warm embrace of one who has been a lifetime lover and the pleasure of being with family and friends. Anyway, I’m suggesting that every life needs to be affirmed, whatever the age or condition.

And staying within family experience for another moment, I think of Lee’s wonderful son Chris who died recently from cancer. There was no “rage, rage at the dying of the light” for Chris. Chris reported that he spent a lot of time at the end thinking of all things he had to be grateful for. He was not a church person but I would describe that as a Eucharistic response. Gratitude, being thankful, can be a powerful force, a life affirming force even in the face of death. Mary Jo Leddy wrote a whole book about gratitude and wholeness.

Well, in contrast, there are terrible things going on in our world. Like many of you, I’ve been watching a lot of television and doing a lot reading about the war in the Ukraine including many stories about heroic women and men struggling to stay human when everything human is under assault. One is staggered by the question of how relationships between Russians and Ukrainians can be healed, relationships that have been shattered by all the brutality. Len Desroche has spent a lifetime pointing to the futility and barbarity of war. Loving not hating your enemy is the only way in Len’s view. Is this an impossible demand made by Jesus or, is it the only route to a genuinely human world, perhaps the only route to human survival?

Love is not just an emotion though emotion certainly comes into it. It’s a response of the whole person and there is something circular or reciprocal here. Love is a gift to which we respond and that gift enables us to love in return. It’s empowering. That’s the gift that Mary Oliver talks about in that poem read earlier. That gift is the heart of the Gospel. And the resulting power can extend, it seems to me, to loving your enemy .I don’t know how you can love your enemy if you have not experienced love at a very profound level.

Most of us, in our personal lives, know about this reciprocal experience of love. It seems to me that that personal experience of love is stretched, challenged and sometimes even reinforced when we enter into community. When we all used to gather around the altar at the Eucharist (and I hope we will do this again in the not too distant future) we would acknowledge our brokenness as individuals and as a community and the bread and wine were signs of a healing power in our midst. A healing power that can enable us to live eucharistic lives, live that was on a daily basis.

Lee and I live on Bloor street, across from the Church of the Redeemer. At a certain moment each day, the Redeemer’s bell rings out, a joyful reminder of all that I’ve been saying, rings out on a busy street in downtown Toronto. When I walk across Bloor street, I try to make a practice of carrying money to give to street people who are begging for it. Despite my lousy hearing, I usually try to engage in conversation as I make my small offering and I’m struck by how faces light up when words are exchanged as well as money. When I’m walking back there is often a wave of recognition from the person whom I had previously encountered and talked to. Well, this certainly isn’t solving the problem of poverty – which is huge – but it’s a reminder of the importance of encounter at a human level. It’s a matter of a person feeling recognized. There’s a whole book here about the importance of feeling recognized – and its connection to healing and feeling like a whole person, a person someone cares about. Of course, we need to address the problem of poverty as a public policy issue but if there isn’t a human, caring element in the process, a human exchange of some sort, it will be cold comfort for sure.

To pursue the question of “recognition”. for a moment: I remember an older person in the congregation – since deceased -an older person who had been deeply committed to social justice telling me about a younger person (no longer in the congregation) who was also committed to social justice causes, but who seemed to treat him as though he didn’t exist. He found this both perplexing and hurtful. Maybe it was unintentional on the part of the younger person but how often in our society do people feel invisible, of no account, in the eyes of others. Remember Ralph Ellison’s book about his experience as a black person? The title of the book was “Invisible Man.” A very important question. Have you ever felt this way: that in some social gathering that you were in effect invisible, that your words were simply not heard? Hardly an affirmative experience.

How does forgiveness fit into this account of healing? Some who have studied world religions have said forgiveness is the distinctive feature of the Christian faith, the distinctive teaching of Christianity. It’s certainly prominent. Think pf the prayer Jesus taught us. The words of that prayer may slip off our tongues as a matter of habit but in many circumstances, asking for and granting forgiveness is no small matter. What if a person has inflicted a hurt but won’t or doesn’t acknowledge it?. Or what if the “apology”seems empty to the person or group that has been hurt? In the program I watched last night some of the indigenous spokespersons were totally unconvinced by the apologies offered. Forgiveness was not what they felt – rather a sense that the people who ran the residential schools and abused the children to the point of burying them in unmarked graves, knew exactly what they were doing, and that, they felt, was unforgivable. I offer another case, the Holocaust? For many Jews, forgiveness is out of the question. Justice of some kind, perhaps, but not forgiveness. The question arises in many contexts – I’ve already mentioned the war in the Ukraine. But if reconciliation is not possible, are we not left with endless animosity, in some cases leading to violence and maybe ultimately to mutual destruction?

The impulse for revenge is ever so strong for us humans. Reading novels, watching the news on Television, don’t we, almost instinctively, identify with a person or a group seeking revenge when they have been wrongly treated? In contact sports, it’s seen as totally appropriate to retaliate when a teammate has been hit – the fans roar out their approval. Revenge successfully meted out. But on a larger human plane: revenge or forgiveness: Which will make things right? Some time ago, during the civil war in Nicaragua, a very important prisoner was brought in to face the Minister of Public Security in the very early, good days of the Sandanista regime. The prisoner had previously beaten up the Minister he now faced. The Minister (whose name I can’t rcall at the moment) said, I take my revenge thus – placed a kiss upon the prisoner’s cheek and told him he was free to go. A very moving, powerful story.

Forgiveness, healing, wholeness: these are closely intertwined. And the gift that makes all that possible is the heart of the gospel. It is empowering even in the darkest situation.