By Len Desroches

August 7, 2022

To someone like MLK or Dorothy Day reading the gospels is an affirmation of radical nonviolence. There are also scripture scholars who have a personal commitment to reading the gospels from the perspective of radical nonviolence.

Two of these are Walter Wink and Clarence Jordan. Wink once expressed his perspective this way: “Violence simply is not radical enough, since it generally changes only the actors but not the way power is exercised.”

So highly respected is Wink’s work that he was once asked to join South African church leaders in exploring the meaning of revolutionary gospel nonviolence in South Africa in the period of apartheid. During his explorations he made some fascinating and crucial discoveries about the passage in the gospel according to Matthew chapter 5, verses 38-44. Here Jesus challenges us to love our enemies. But just before that, he talks of turning the other cheek. This is a passage that has too often been seriously misrepresented as a call to pietistic passivity in the face of injustice. Consequently, by the time we hear the words “Love your enemies,” they have been neutered by this spirit of debilitating passivity.

Let me quote the passage to you from a standard English translation, the King James Bible: “You have learnt that it was said: An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. But I say to you: Do not resist one who is evil. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also; and if anyone would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well. And if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles…you have heard that it was said: You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy. But I say to you: love your enemies.”

Walter Wink took a close look at the abused passage in Matthew in a short work entitled: “Violence and Nonviolence in South Africa – Jesus’ Third Way.” I will quote from this work at some length because his insights are so foundational to an understanding of power in the context of nonviolence. In it he observes:

“When the court translators working in the hire of King James chose to translate “antistenai” as “resist not evil” they were doing something more than rendering Greek into English. They were translating nonviolent resistance into docility. Jesus did not tell his oppressed hearers not to resist evil. That would have been absurd. His entire ministry is utterly at odds with such a preposterous idea. The Greek word is made up of two parts: anti, a word still used in English for “against” and “histemi” a verb which in its noun form (stasis) means violent rebellion, armed revolt. Thus Barabbas is described as a rebel “who had committed murder in the insurrection.”

A proper translation of Jesus’ teaching would then be, “Do not strike back at evil in kind. Do not retaliate against violence with violence.” Jesus was no less committed to opposing evil than the anti-Roman resistance fighters. The only difference was over the means to be used: how one should fight evil.

There are three general responses to evil: 1) passivity, 2) violent opposition, 3) the third way of radical nonviolence articulated by Jesus. Human evolution has conditioned us for only the first two of these responses: fight or flight. “Fight” had been the cry of Galileans who had abortively rebelled against Rome only two decades before Jesus spoke. Jesus and many of his hearers would have seen some of the two thousand of their countrymen crucified by the Romans along the roadsides. They would have know some of the inhabitants of Sepphoris (a mere three miles north of Nazareth) who had been sold into slavery for aiding the insurrectionists’ assault on the arsenal there. Some also would live to experience the horrors of the war against Rome in 66-70 C.E., one of the ghastliest in human history. If the option “fight” had no appeal to them, their only alternative was “flight”: passivity, submission. For them no third way existed. Submission or revolt spelled out the entire vocabulary of their alternatives to oppression.

Now we are in a better position to see why King James; faithful servants translated antistenai as “resist not.” The king would not want people concluding that they had any recourse against his or any other sovereign’s unjust policies. Therefore the populace must be made to believe that there are two alternatives and only two: Flight of fight. And Jesus commands us, according to these king’s men,to resist not. Jesus appears to authorize monarchical absolutism. Submission is the will of God. Most modern translations have meekly followed in that path.

Neither of these alternatives has anything to do with what Jesus is proposing. It is important that we be utterly clear about this point before going on: Jesus abhors both passivity and violence as responses to evil. His is a third alternative not even touched by those options. Antistenai may be translated variously as “Do not take up arms against evil,” “Do not let evil dictate the terms of your opposition” The Good News Bible translates it helpfully: “Do not take revenge on someone who wrongs you.” The word cannot be construed to mean submission.

Then Wink goes on to a fascinating analysis of the three examples of nonviolent resistance given by Jesus. He shows how when Jesus refers to the turning of the other cheek, he is talking not of a fis fight, but of a backhand slap that was (is) the normal way of admonishing inferiors.

[demonstrate with another person: turning the other cheek in an invitation to enter into an equal relationship – an insistence on one’s dignity]

Wink notes:

Masters backhanded slave; husbands, wives; parents, children; men, women; Romans, Jews. One black African told me during his youth white farmers still gave the backhand to disobedient workers.

We have here a set of unequal relations, in each of which retaliation would be suicidal. The only normal response would be cowering submission.

It is important to ask who Jesus’ audience is. In every case, Jesus’ listeners are not those who strike, initiate lawsuits or impose forced labour, but their victims (“If anyone strikes you…would sue you…forces you to go one mile…”). There were among his hearers people who were subjected to these very indignities, forced to stifle their inner outrage at the dehumanizing treatment meted out to them by the hierarchical system of caste and class, race and gender, age and status, and as a result of imperial occupation.

In other words Jesus talks most directly to the unemployed, the homeless, the person with AIDS, the stigmatized ex-prisoner. These people always experience their own power when their battered, barely conscious dignity is awakened and healed. They instinctively recognize this as genuine, God-given power. Christ’s message is clear: God’s life is withing you and you have a claim to full participation in the Beloved Community.

Jesus is calling us to insist on our dignity – equally in the other two examples:

If a rich person takes your outer garment and takes you to court because you haven’t yet been able to pay a debt, then dramatize – with full dignity – how unjust this all is by giving him your inner garment as well! This is similar to when Francis of Assisi stripped naked in a statement of dignity and of freedom from his father’s wealth and control.

And what about the example of walking a second mile? As an occupying force, the Romans had a law that their soldiers, with all their equipment, could order a Jew to carry his stuff, but only for one mile. At the end of the mile, Jesus says express your dignity, that you are in control of yourself and insist on carrying the soldier’s equipment a second mile.

In all my training sessions that I’ve offered to groups like Peace Brigade International or Christian Peacemaker Teams, I have always referred to dignity as “the first power” of nonviolence. It is difficult for anyone who has been generally treated with dignity to see anything powerful in what Jesus is proposing. Yet it is what Martin Luther King proposed to angry and frustrated blacks. He could have offered them guns, but instead he challenged them, maybe for the first time in their lives, to stand there with all the power of their God-given dignity when backhanded by the white “boss” – the first necessary step in nonviolent resistance.

Not long after I had begun to call dignity the “first power” in nonviolence, I saw a large glossy poster in a video store. Its large lettering said: “THE FIRST POWER – The perfect killer in the one who cannot be stopped. Be warned.” The large photo showed a perfectly groomed, attractive, calm-looking young male ready and eager to use a gun. I thought: “How accurate. The gun is indeed thee first power of violence and retaliation.” We choose between the two “first powers.”

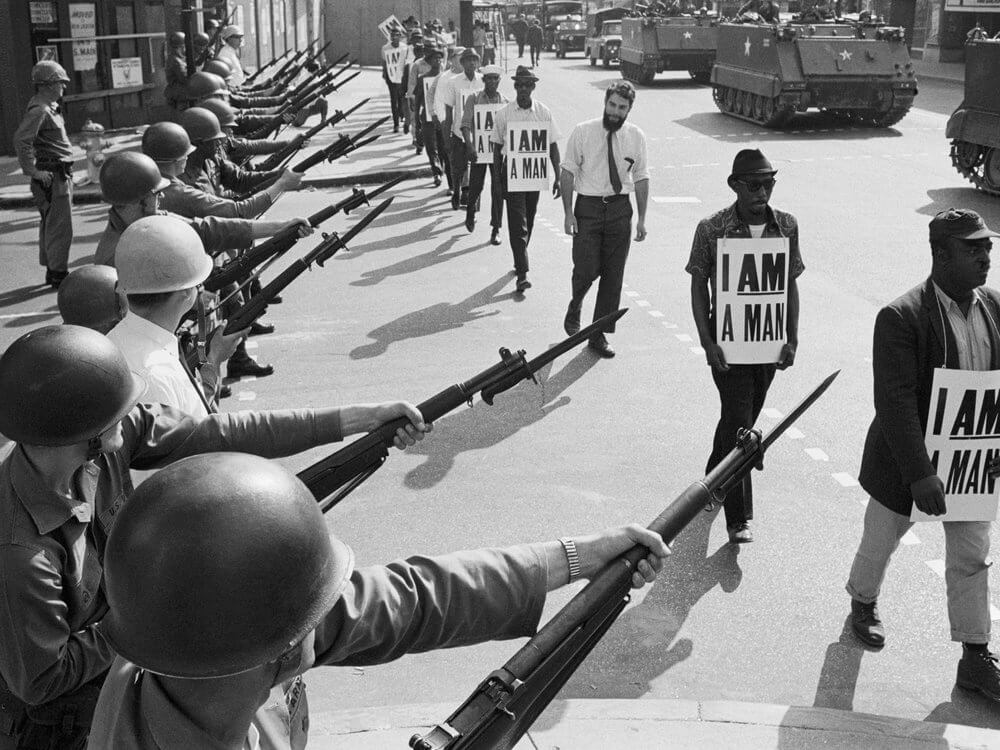

One of the most dramatic illustrations of the contrast between the two “first powers” is a photo taken during the civil rights movement: on the left is a row of soldiers, straight as a concrete wall, bayonets ready; on the right, confronting the bayonets, is a row of black men, walking in single file, with silent, powerful dignity, each carrying a large sign saying simply, “I AM A MAN.”

In calling dignity the “first” power in nonviolence, I acknowledge that it is just the first step. But it is the crucial first step. Without it, without an insistence on one’s dignity, the other steps are not fully possible. Dignity is the beginning of our discovery of the spiritual force behind “nonviolence.” Again, this is precisely the power that Jesus’ listeners experienced when he awakened and healed their dignity. What is this power called dignity? In the context of nonviolence it is the experience of God as Love and the consequent conviction that regardless of status (financial, social, racial, sexual, religious) I am your sister, your brother – whether you recognize it or not.

Now I would like to turn to the end of today’s gospel reading, where it has often been translated as “be perfect.” Another scripture scholar committed to nonviolence examined the original word often translated as “perfect” and found that wherever else it appeared in the bible it had more the meaning of “mature.” The most explicit teaching of Jesus regarding maturity of love is when he says, “I know, I know what you’ve been told, ‘Love those who love you and hate your enemies.’ But I say this to you: Love your enemies, Become as mature in love as God is.”

Regarding spiritual maturity, I’d like to quote Clarence Jordan, farmer and scripture scholar: “There has been much misunderstanding of this verse (Matthew 5:48) because of the translation “perfect” instead of “mature.” …The Greek word translated “perfect” means to have all the parts, to have reached full maturity…To talk about unlimited retaliation is babyish; to speak of limited retaliation is childish; to advocate limited love is adolescent; to practice unlimited love is evidence of maturity.”

We are called by Jesus to become as mature in love as God it.

Amen.

A recent conversation between Len and Culture d’Empathie – Le Podcast, including thoughts on the current war in Ukraine

Episode 12: #12 – Love of enemy with Léonard Desroches – Aimer son ennemi

Léonard Desroches, citizen of Toronto and longtime activist, is a humble and unpretentious man who nevertheless makes waves and moved mountains during his life. He is a man who from a young age felt the call for justice and peace for all human beings and he is an icon of nonviolence in Canada through his many writings and actions.