There’s an interesting moment in the career of Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan general who became Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, when he is parleying with his Scottish opponents and says (I’m paraphrasing), “I beseech you for the love of mercy consider that ye may be wrong”. It’s not included in the record, though one feels it would have been very much to the point if the Scots in turn had besought him for the love of mercy to consider that he may be wrong. Cromwell prevailed in the ensuing flash of certainties and his troopers went on in iconoclastic certitude to stable their horses in Edinburgh cathedral. No doubt many of them took their victory as a God given confirmation that they were in the right.

There’s an interesting moment in the career of Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan general who became Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, when he is parleying with his Scottish opponents and says (I’m paraphrasing), “I beseech you for the love of mercy consider that ye may be wrong”. It’s not included in the record, though one feels it would have been very much to the point if the Scots in turn had besought him for the love of mercy to consider that he may be wrong. Cromwell prevailed in the ensuing flash of certainties and his troopers went on in iconoclastic certitude to stable their horses in Edinburgh cathedral. No doubt many of them took their victory as a God given confirmation that they were in the right.

For me, this Anglo-Scottish vignette from the 17th century illustrates how all prevailing certitudes are deeply suspect. At their extreme the people who hold them are spiritual and/or political terrorists of whatever sectarian stripe, An the dangers of such extreme certainties are so obvious that they hardly need mention; just read a newspaper or listen to the news any day of any week. In the common phrase ‘dead certain’ the operative word is ‘dead’.

There are also less spectacular dangers of less spectacular certitudes. But these also share in the dynamic of closing off-of distinguishing us from them, being in from being out. They tend to limit communication between those ins an those Outs to each party trying to get the other to see things their way, that is, to proselytize–hopefully by persuasion rather than violence. The us / them discourse framed by certainty does not admit doubt.

At my stage in my pilgrimage it seems to me that doubt can serve as a creative, energizing antidote for certainty. Even in its extreme terroristic forms certainty is an essentially defensive posture. It resists the cost, yes even perhaps the risk, of openness, change, new growth. It defends what it regards to be the only turf that’s right. It reminds me of the Maginot Line, that astonishingly long, monstrously expensive, and static system of fortifications that the French built between WW1 and WW2 to keep the Germans out.

The Maginot Line is an apt image of certainty: its function is to be outflanked. The French army’s faith in their fortifications wasn’t open enough to doubt, to the possibility of being outflanked.

Some time ago Sherman forwarded to me a copy of a poem by Yehuda Amichai, a major Israeli poet. This poem’s become one of my favourites that I recite to myself on early morning exercise walks. I love it because it takes account of the wreckage left by self-righteous certitude, because it recommends doubt, and because it leaves us with a whisper of the possibility of renewal:

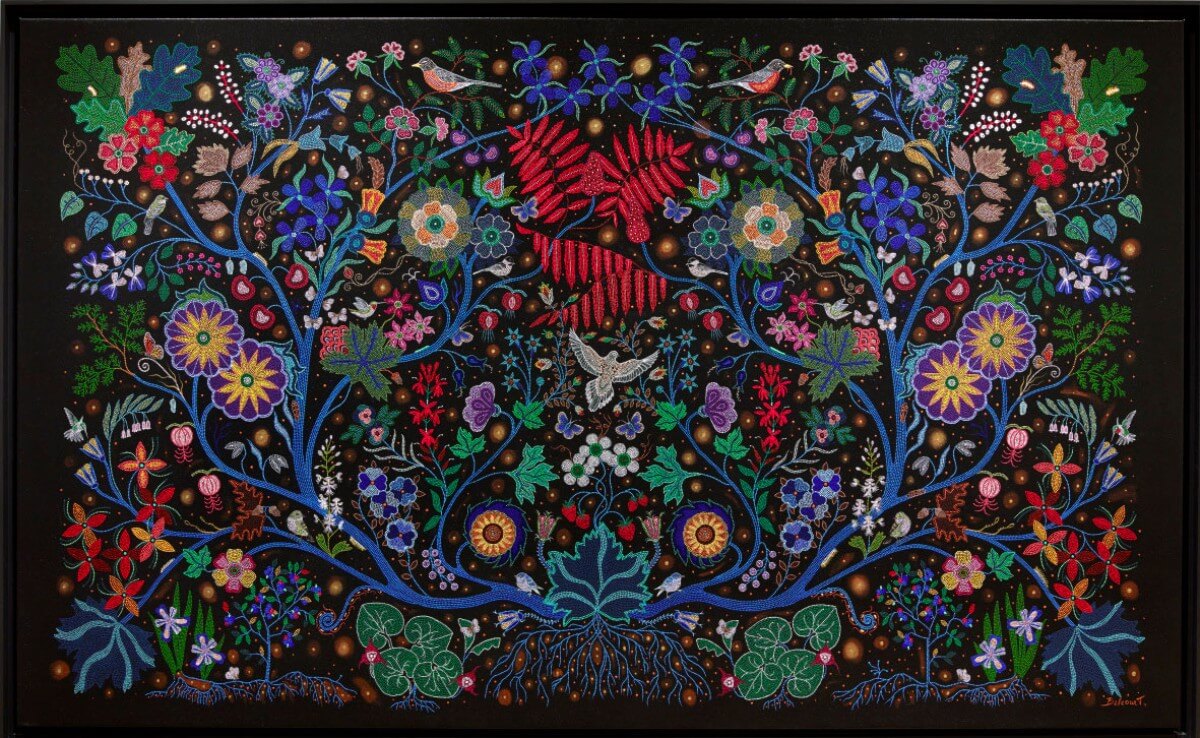

THE PLACE WHERE WE ARE RIGHT

From the place where we are right

flowers will never grow

in the spring

The place where we are right

is hard and trampled

like a yardBut doubts and loves

dig up the world

like a mole, like a plough.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

where the ruined house once stood.

Yehudai Amichai

The term “faith communities” usually serves as a descriptive identifier of religious groupings-Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, Christians in their various sub-groups, and so on. I find a community that lives by faith to be a useful spin on “faith community”. “Lives by faith” means precisely being open to doubt, not living behind static, defensive certainties. For its good digestion faith needs the grist of doubt.

At this point let’s revisit a couple of passages in the lessons we’ve just heard. In Jeremiah 31 there are those visionary words about the covenant being internalized so that there’s no need to live under the strictures of an externally impose law. This is indeed a truly prophetic message but it does not necessarily emancipate the covenanter from doubt. It reminds me of the 17th century puritan theological emphasis on the ‘inner light’ that frees believers from the impossible-to-satisfy demands of an external, institutionally sanctioned set of dogmas. This theological emphasis was espoused

by John Milton (and Oliver Cromwell as for that matter). And for Milton too, the ‘inner light’ does not necessarily emancipate one from doubt. Is that light always reliable as the diving promptings

of God’s will or is it vulnerable to being confuse with one’s own will? In his poetic drama Samson Agonistes Milton deals with this problem. Samson has paid the price of confusing his own will to

hang out with Delilah with the will of God. The action of Milton’s poetic drama shows Samson working through the difficult process of realigning his will with the will of God and, with his confidence

and clarity of purpose restored, reaching the moment of commitment worth dying for. But it has been a real struggle, a real agon.

Then in the Gospel passage from which, just between you and me, I find rather muddled – [the enquiring Greeks, Philip and Andrew all just disappear abruptly from the narrative; what

happened to them? The whole passage seems to be betwixt and between the narrative of events on the one hand, and an the other, the sometimes very long meditations / prayers / disquisitions that the gospeller assigns to Jesus. And Jesus’ reply to Philip and Andrew seems to take no regard of the request to be introduced to him.] Anyway, for the moment what I find very germane in the

passage is Jesus’ striking moment of doubt: “Now my soul is in turmoil, and what am I to say?….” Jesus is portrayed as quickly recovering a good measure of authoritative equilibrium, but for me

that moment of doubt clearly adumbrates the coming agon in Gethsemane. Jesus’ lenten journey is rapidly gaining momentum towards Gethsemane, a rigged trial, and a religio-politcal murder; and in this passage he clearly has strong intimations of the fate awaiting him.

In Gethsemane, almost as moving as Jesus’ agon, his agonizing wrestle with doubt, is the disintegration of his community. We know, though, that neither the doubt nor the disintegration of a supportive community is the end of the of course in no way detracts from the immense power of the lenten narrative.

Where is there any prospect of restored, life-giving community? There are of course demonic communities ferventîy devoted to destroying or incarcerating or banishing anyone whom they label

as heretical enemies. Well, by their fruits ye shall know them. Then, too, there are uncommunities of one, fervently devoted to an entirely self-serving, self-centred existence-the kind of life

Vaclav Havel characterized as de-moralized (cited by Michael Creal in last week’s homily). But now I am closely approaching Michael’s concluding emphasis on community in that homily of last Sunday. Is there a promise of such a living-by-faith community? a plurality within which I can, paradoxically, most fully be my singular self?

The always coming-to-be of such a community is a person, Jesus-the-Christ. I understand myself to be both a Jesus-follower and a Christ-bearer. Being among fellow Jesus-followers and Christ-bearers is my faith community. We try to follow Jesus even when the going is tough and that Jesus, who is the living Christ, rises again in us and among us every day. My pilgrimage so far has

brought me to where, gathered with you in a circle around this Eucharistic table for the sacred meal, the overtones to the words I hear are: “Whenever you specially want to recall that I am risen

and present among you and in each of you, do this.”

At this sacred meal of celebratory remembering, faith and doubt can kiss and be guests together.