This past week, I posted a short note on the Holy Trinity e-list with observations from my past weekend at Canterbury Cathedral – the ‘Mother Church’ of the worldwide Anglican Communion.

As we are in the midst of a conversation here at Holy Trinity on liturgical formation – how we shape and express our faith in worship services – Lee very kindly invited me to share a few thoughts from Canterbury this morning. We will continue the conversation after the service in our adult forum.

It was my first visit to Canterbury, and I was pleased to be able to sit in the quire for Evensong on Saturday afternoon and then Sung Eucharist on Sunday morning.

As you might imagine, I was especially delighted to be invited afterwards to share a glass of wine with the Archbishop of Canterbury and a couple of dozen ‘baby bishops’ who were gathered for an annual conference for bishops who had been in office for less than a year.

Since we live in the 21st century, and are as a society obsessed with the mere fabric of celebrity – let me begin with a fashion statement: The vestments worn by Archbishop Justin are without a doubt much more high end than anything here at Holy Trinity, though perhaps this is to be expected.

However, if I may say so, the altar cloth here at Holy Trinity beats its counterpart at Canterbury in both style and substance. Throughout the course of the year, we have an absolutely splendid series of altar cloths.

Suppose, at this point, I was to interrupt this homily by inviting you to open the red hymnal to number 291 (number 251 in the Anglican Hymnal) and join with me in the singing of ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ as a means of creating a link between here and Canterbury.

At Holy Trinity we don’t often use this hymn, but much of our parish, along with our sisters and brothers in Canterbury, would certainly recognize this hymn. Rupert Christiansen, in his delightful book ‘Once More With Feeling: A Book of Classic Hymns and Carols’ calls ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ a “hugely popular but faintly nauseating little Sunday School hymn for infants”. The tune is from a traditional melody in 1660 that celebrates the restoration of the English monarchy under Charles II:

<< play refrain on accordion here >>

I was shocked and all of you here today will be somewhat surprised to learn that the accordion does not feature prominently in worship at Canterbury. Here at Holy Trinity, we are regularly blessed with the sacred squeezebox – sometimes even monthly. So, score another point for Holy Trinity ahead of Canterbury.

Incidentally, I am sure that both here at Holy Trinity and there at Canterbury, most are pleased that the second verse from the original version of ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ by Mrs. Cecil Frances Alexander has been dropped. It reads:

“The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them, highly or lowly,

And ordered their estate.”

In the 21st century, as we grapple as a church and a society with growing inequality and its social, economic, political and health impacts, a 19th century expression of social order is no longer appreciated or even welcome.

I mention this because, though it sometimes seems that we Anglicans are unduly chained to the old ways, I do believe that change is not only possible, but it is necessary and that it can and does happen in our church and in our liturgy.

This change is not just the dropping of a controversial verse from an older hymn, but in the way we approach and express our faith in our liturgy.

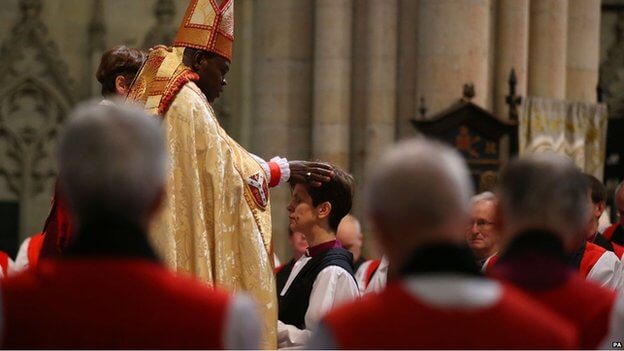

Back to Canterbury: Several at the Eucharist last Sunday expressed a mild shock that there was a woman amongst the ‘baby bishops’.

It is startling for us at Holy Trinity to consider that the first woman bishop in the Church of England was ordained on January 26, 2015. That’s right, two weeks ago.

Check out the on-line video of the magnificent ceremony – and then look at the short video biography of Bishop Libby Lane posted by the Church of England.

During the ceremony, the Archbishop of York turns to the full house at York Minster and asks if it is their will that Libby Lane be ordained. The answer is loud and sure: It is. But then, a lone voice – a dissenting Anglican priest – stands and says ‘Not in the Bible’ and insists her gender is a barrier to her ordination.

When it comes to the ordination of women, or almost any other subject, it is possible to cobble together a collection of Biblical verses and some cultural practices, and wave these around as if the fierceness of our proclamation and the mere fact that the Bible is invoked will prove the validity of our argument.

Thankfully, that was not allowed to happen on January 26th at the ordination of Libby Lane.

The Archbishop continued since the lone objection based on gender was not a true impediment, but the disruption is disturbing. The Church of England has debated for years the ordination of women bishops and, in the words of the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams:

“As Anglicans we believe that there is one priesthood and one only in the Church, and that is the priesthood of Jesus Christ… The commitment of most Anglicans to the ordained ministry of women rests on the conviction that… makes it inconsistent to exclude in principle any baptised person from the possibility of ordained ministry.”

Yes, change does happen. Sometimes too timidly and much too late, and with painful disruptions. But it comes.

Canterbury Cathedral was founded in 597 AD when a monk named Augustine was dispatched by Pope Gregory the Great to evangelize the English. There was already a native Christianity in England – Celtic or Gaelic Christianity. The so-called Creed of St. Patrick begins:

“Our God, God of all men,

God of heaven and earth, sea and rivers,

God of sun and moon, of all the stars,

God of high mountains and of lowly valleys,

God over heaven, and in heaven, and under heaven.

He has a dwelling

in heaven and earth and sea

and in all things

that arc in them.”

Author Christopher Bamford says: “In these words of St Patrick has been seen an epitome of the Celtic monk’s holy embrace of nature, his sense of ‘ecology’”. While this ecological spirituality was diminished when Roman Christianity started its sweep over the British Isles with the arrival of Augustine, it was never lost. Even ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ has a greenish tinge that celebrates the beauty of the natural world, the created world.

Here in North America, Christians are rediscovering a theology of nature as we work with our indigenous sisters and brothers towards spiritual renewal.

Canada’s National Indigenous Bishop Mark MacDonald says that his appointment “re-thinks the relationship of Christian faith and aboriginal identity and authority” and “re-imagines the relationship of a community of faith with the environment.”

He goes on to say that a truly indigenous Christianity includes a:

“re-conception of the communion of God and humanity as essentially a communion between God and Creation. This communion is conceived as a dynamic ecological relationship between all that is and the Creator. Humanity plays an important but entirely dependent role – dependent upon the integrity of the web of life itself, with Spirit at the centre.”

What we would today called the ecological consciousness of the Celtic Christian church was diminished with the arrival of the Roman mission at Canterbury at the end of the 5th century, but it was never lost. And that’s because thinking, searching Christians never let it be lost.

I experienced one beautiful dimension of that reverence for the world and for light during the Sunday service at Canterbury. Normally, candlemas is celebrated on February 2, but this past Sunday we processed through the magnificent cathedral from quire through the nave to the spectacular 17th century font with each of us holding a candle to light our way.

Christians celebrate candlemas as the presentation of Jesus in the temple on the 40th day after his birth. Traditionally, candles that are used throughout the year are blessed on this day. Candlemas builds on a Christian event drawn from the Jewish calendar of purification. It also falls halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox – an auspicious time in the early Celtic and pre-Chrstian calendar that marks the return of life-giving sun to a cold northern climate.

Folk traditions tell us:

“If Candlemas Day be fair and bright

Winter will have another flight

If on Candlemas Day it be shower and rain

Winter is gone and will not come again.

In parts of Europe, people have turned to badgers as furry weather prognosticators and here in North America, we look to the noble groundhog.

At this time, at Holy Trinity, we are affirming, rediscovering and translating into the 21st century a spirituality rooted in early Christian and pre-Christian roots when we open our doors to events such as the Keepers of the Waters vigil on January 15, 2015. Our faith, and its expression, is not stuck in time or geography.

Though it can be frustratingly slow to change, change does come to our church and its practices.

Let’s fast-forward by half-a-millennium from Augustine of Canterbury in 597 to Anselm of Canterbury in 1093.

Anselm’s motto is “faith seeking understanding”. He taught us that our human brain, our capacity for rational thought, was given to us by God for a very specific purpose – and that is to use our brains actively and deeply.

Some suggest that our brain be turned off when it comes to matters of faith. Not so for Anselm. He tells us:

“It is a certainty, therefore, that rational nature was created to the end that it should love and choose, above all, the highest good, and that it should do this, not because of something else, but because of the highest good itself.”

Not only should we actively use our brains, but we should strive to channel our rational energy towards that greatest good, love. Don’t check your critical faculties at the door when you walk into Holy Trinity, or Canterbury.

So, yes, we must need to continually ask why we say the words we say, and sing the hymns we sing, and practice the liturgies that we practice. And we need to continually use our brains to drive our faith and our practice towards that highest good that is within our reach.

Finally, I want to skip forward another half a millennium from Anselm to Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1532. He was the leading figure in the English Reformation and a guiding light of the early Anglican church. His thinking inspired and provided the foundation for the 39 Articles of our faith in 1562.

Some call the articles ‘latitudinarian’ – that is, they are meant to be read with wide latitude and great tolerance. Or, as Anselm might have said, we need to bring our brains to bear when we consider the 39 articles.

Article 19 tells us that the church is the visible congregation of faithful persons – and warns us that the church is capable of error (all human structures are capable of error). We hold in the greatest respect the thinkers and the practitioners, the mothers and fathers of our church going back many generations. And we respect the structures established to provide governance to our church. But we do so with our eyes open, and our minds fully engaged.

Article 24 tells us in strong language that it is “plainly repugnant to the Word of God” that church liturgies should be conducted in a language not understood by the people. While a common and understandable language is the start of an engaged liturgy, we also have to ensure that the liturgy reflects the wisdom, culture and experience of the people, as well.

As we carry on our conversation, in just a few minutes, on future liturgical evolution here at Holy Trinity, what is the intelligent construction that we can place on these two important articles of our Anglican faith:

First, take care with any human institution, including the church. Just because things have been said or done in a certain way for a certain period of time doesn’t make them right or good. Nor do we simply toss aside old practices just because we are bored or tired.

Second, make sure that our liturgical expression arises from our cultural and spiritual understandings. Our words and our expressions need to make sense and to draw from our lives, our culture, our experiences and our understandings.

Let me end by saying my first visit to Canterbury Cathedral will not be my last. More than 1,500 years of continuous worship has helped to create a truly holy place that inspires me, and many others who walk through the glorious building and engage with its history and spirit. Canterbury also awakens my mind and causes me to search more deeply about my own faith, and our collective expression of our Christianity.

I pray that as we continue our conversation on the visible practice of our faith, we will be guided by the twin pillars of deep and abiding love, and an intelligent and reasoned critical mind.