By Susie Henderson

Readings:

- Isaiah 61: 1-4, 8-11

- The Sweetness that Remains: Orange Blossom Honey Blessing in The Cure for Sorrow: A Book of Blessings for Times of Grief by Jan Richardson

- John 1 :6-8, 19-28

ROSEMARY FOR REMEMBRANCE

They say that grief is the tax on love — if you love you grieve, no getting around it. I brought rosemary today to honour the losses that we all carry and may be particularly mindful of at this time of year.

Rosemary — has a long history and there are many stories tied to this fragrant herb. Historically it has been thought to strengthen memory and that tie to remembrance and it has been included in both the wedding bouquet and the funeral garland.

Medicinally the camphor in rosemary has helped to clear congestion. In our house it mostly comes out with a little lemon to season Jennifer’s favorite roast chicken.

Today I offer it as a sign of remembrance, a scent that lingers, a way to witness that death is not the end of love. Death is not the end of love.

During this reflection, I invite you, if you’d like, to come forward and make yourself a mini wreath of remembrance that you can take home for a christmas tree or to place somewhere in your line of sight, a sign of the presence of those who have gone before us, still present, still missed, still remembered in our holiday times. You can make it during the service or just pick up the pieces to put it together when you get home.

REMEMBERING IS AN ACT OF RESISTANCE

Almost everything about western colonial culture pulls us to move away from the dead and remembering feels like an act of resistance. Sometimes this tide starts tugging at us even before the death has taken place. And after a death we can drift aimlessly without anyone to guide us. We’ve lost our memory of how to care for the dead, even simple things like washing and dressing people is not usually a part of our practice today. We are used to having funerals without caskets. We spend little time in the graveyard. In some cases there are no funerals at all. Vulnerable people are just disappeared. There is little room for mourning and stopping to remember in the fast moving world where we live. I think the absence of these rites reflects a bigger fracture in the culture in the relationship between the living and the dead.

Many contemporary grief therapies include a mourner’s “to do list” that is about accepting the loss, re-adjusting our lives without the deceased and re-investing in other relationships. To dwell, to remain undone, to continue to long for someone’s presence after the ‘acceptable period of mourning’ — whatever that is — is to risk being judged, or diagnosed.

It’s true that letting go is a big part of what mourning is about, and it’s unavoidable. But there is a strong unstated bias in that thinking that comes from imagining people as autonomous individual selves who exist independently of each other, who patch themselves up and move on. (Hedtke and Winslade, Re-membering Lives: Conversations with the Dying and the Bereaved). But I don’t think broken-hearts are necessarily mended by letting go and moving on. Somethings can’t be fixed, they can only be carried (http://www.refugeingrief.com/) I think that hearts are healed by carrying our losses and coming together as community that re-members the dead as well as looks to the future.

I have kind of outed myself as someone who lives with life-long grief, beginning with the loss of my mom when I was a young woman. I’ve always felt marked by loss, it always comes around, sometimes predictably at a time of year when I anticipate it, and sometime it sneaks right up when I’m not looking. And it is not something that returns with gradually less intensity. Sometimes my grief about my mom is sharper now than when it was fresh, cutting deeper into parts of life that I never even knew I would miss when I was 22.

Whenever I speak about grief publically I am always aware that people hold these stories just below the surface. Maybe you are holding one now. And there are so many crappy things that we say to each other about it — so many that now people publish lists of ‘what not to say”. That phrase, some things cannot be fixed they can only be carried is from Megan Divine who has a website called “grief support that doesn’t suck. Jan Richardson, who we’ve been reading this season, has a compilation of writing on grief. Here’s a bit of her advice:

Do not tell me this will make me more grateful for what I had. Do not tell me I was lucky. Do not even tell me there will be a blessing. Give me instead the blessing of breathing with me. Give me instead the blessing of sitting with me when you cannot think of what to say.

Give me instead the blessing of asking about him—how we met or what I loved most about the life we have shared; ask for a story or tell me one because a story is, finally, the only place on earth he lives now. If you could know what grace lives in such a blessing, you would never cease to offer it. If you could glimpse the solace and sweetness that abide there, you would never wonder if there was a blessing you could give that would be better than this—the blessing of your own heart opened and beating with mine.

She says that the blessing is simply that broken-hearts go on beating. I was reminded of that when Jim spoke last week about simply being able to take a breath in the midst of despair.

Years ago when Monica and I were in Aotearoa New Zealand I was struck by the Maori practice of greeting each other in song. Two groups approach slowly, with responsive singing, back and forth until they stand face to face, guest and host. We asked what the songs meant and it was explained to us that they sing about their ancestors and the places that they come from, their sacred mountains and rivers. They say they carry their ancestors on their shoulders. So the meeting is much more than two groups of people, but an awareness of a great company of relationships that are all carried and require introductions. As if there are layers of people arriving to the feast and only some of them come in bodies.

In the Christian tradition we generate that kind of great company as well when we process in the litany of saints, that big roll call the ancestors in faith and struggle who we carry on our shoulders. Elizabeth Johnson talks about the litany of saints as a way of creating a dynamic solidarity, backward through time, that encourages the living to carry on. There’s a power to be held from gathering the cloud of witnesses – it’s more than a private act of remembering can conjure. It’s more than reminiscing.

Litanies of remembering draw down deep roots spiritual roots. Our stories become thicker when they are intertwined with the dead. This kind of connection is not possible, or it is seriously thinned out, in the paradigms where grief is resolved.

WWOS

Recently I had the privilege of being a part of hosting The Walking With our Sisters ceremony, a commemorative art installation to honour missing and murdered indigenous women. Families and friends of women who have been murdered or gone missing have created and contributed over 1,000 moccasin tops, called vamps, that have been gathered into what is known now as ‘the bundle’ — a travelling ceremony that is moving through communities across Turtle Island for seven years.

At all times the bundle is protected and held in ceremony. The care and attention began when the boxes were unloaded from the truck with singing and drumming as they were passed along the line of volunteers. Each community comes up with their own design for the installation. The Toronto pattern was set out in the shape of the milky way based on a vision of one of the grandmothers. It took five days to prepare the space before the lodge was set up so that people can walk through and pay their respects, honour their losses. The boundaries of the site are marked with tobacco. There are keepers appointed to ensure the protocols are followed each day. There are always grandmothers present when the installation is open to the public. The bundle was feasted at the beginning and the end and a sacred fire marked these times. The volunteer team met at the beginning and the end of each day in a circle to open and close the ceremony, always with a purifying smudge of sage. Volunteers were expected to uphold a space with kindness and respect. One evening a grandmother invited us to sing a lullaby for our sisters, to offer them some sweetness, a sweetness that many of them had been denied in their lives and certainly in their deaths. All of these acts of loving kindness created a container — to honour the spirits of the dead and to hold the grief of families and friends who are still without any kind of peace. For some it is the only funeral they ever have.

A few things have really stayed with me since that time. It was incredible to witness a cultural practice of people who are ceremonially alive, who take seriously the commitment to care for the dead.

I was also really struck by the power of the work as a whole. When you step into the lodge and are met by the sight of more than 1,000 moccasins, the loss of life is staggering. But the act of bringing them together, of collecting the individual stories and drawing them into one bundle, creates a sacred company, it restores honour and blessing. We enjoyed the idea of the sisters being in one another’s company.

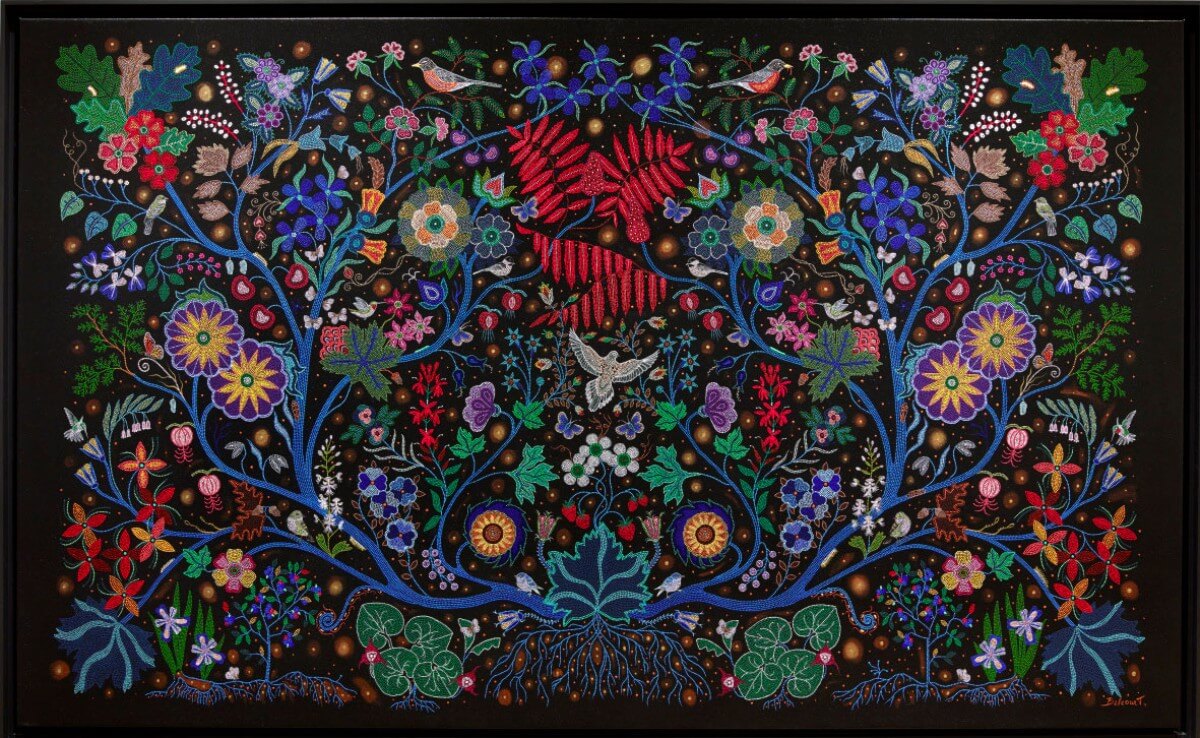

Finally, the vamps themselves are heart-breakingly beautiful. The beadwork, the handwork, the materials, the symbols — strawberries and rivers and stars. Messages of longing and love, anger and sadness. One of my friends that went through said she saw every story she’s ever heard represented in the lodge. These artful acts of memory are mending community — by creating beauty, by releasing sadness and anger, by drawing so many people together, by honouring with the best kind of attention we have, we mend the world, albeit in a small way.

REMEMBERING THE WORK OF OUR HANDS

Remembering is not just something we do with our heads, it’s more than thinking or what we say. It is also the work of hands and hearts. It comes with a tune, with texture, a taste, with a scent. I’ve been taught to believe that it runs in our blood. It’s something to engage, to create.

Ceremonial acts of remembrance, like Walking with our Sisters, like the faithful witness of the homeless memorial, like the ghost bikes that are placed around the city when a cyclist is killed, like the flowers and candles that are amassed when a community grieves a sudden loss — are generative. They create a connection to those who have gone before us. They forge new bonds of kinship and create hope for the future.

I began by acknowledging that anyone who loves will grieve. Loss is something universal, but not only personal. Remembering together is a political act. The Christian story is grounded in this kind of politic — recalling the death and resurrection of Jesus, the one who was put to death by the state and the religious authorities — overturns the legitimacy of those powers. In the same way when we call presente — present with us — when the names of the human rights martyrs are called we delegitimize the powers that put them to death. As it is said of Berta Cáceres the Indigenous leader murdered for protecting water in Honduras — she did not die, she multiplied.

This morning’s readings from Isaiah and John both intertwine mourning and memory and liberation.

That bold mandate for liberation, inspired by the Spirit — good news to the oppressed, liberty to the captives, release to the prisoners and binding the broken-hearted — promises reparation to the mourners — the redistribution of wealth inherent in Jubilee, comfort, a garland, gladness and a mantle of praise. This is not the paradigm of resolved grief here — the mourners are not dismissed here.

They will be called oaks of righteousness,

the planting of God

They shall build up the ancient ruins,

they shall raise up the former devastations;

they shall repair the ruined cities,

the devastations of many generations.

The mourners, alongside the oppressed, the captives, the prisoners are the planting of God, the ones who build up, raise up and repair. Here mourning is bound together with resistance and transformation. The call is to mourn and organize, remember and act. It is both personal and political. Who better to do this work of repairing than the ones who understand the devastation? Jesus carries this call of Isaiah, this promise to mourners, on his shoulders.

The story of John is also alive with memory. The wilderness prophet carries the memory of the prophet Elijah — the story is very clear to point out that he is standing on the banks of the Jordan. His listeners would remember the fantastic story where Elijah was raptured right up to heaven from the banks of the Jordan. The place itself carries memory. So they ask, are you Elijah, they ask? No, he says and echos the words of another ancestor in the prophetic tradition, Isaiah — I am the voice in the wilderness. This story is about carrying the ancestral memory of the prophetic tradition, a wild call from outside the established order. John’s baptisms on the riverside were a far cry from the public baths in the settled places. John’s call is literally grounded in the past, but pointing toward the future — it’s that now and not yet tension of advent. The story is building toward the indwelling of God, but we are not there yet — and yet we are. We are in the in the midst of here.

And we mourners know that here matters. The losses, the loves, the kinship, the struggles, they are not just backdrop for the bigger thing that God is doing. It is what God is doing. The stories are alive. The tales we remember, tell and pass on to the next generation are embedded with energy and are life-giving sources for survival and resistance. In the midst of us, some things don’t get fixed, not everything is resolved, they can only be carried. And at the same time, there is a sweetness that remains, a beauty that shines through, a wild blessing to be tasted, a struggle that continues, maybe a new voice in the wilderness to be heard.

I’ve tried to tie together these threads of memory, mourning and liberation. In addition to the words, I did bring you a taste and I invite you after the service to enjoy a bit of rosemary bread, for remembrance, with a little orange blossom honey, for sweetness.