Final homily by Sherman Hesselgrave, Trinity Sunday, June 7, 2020

Readings: Deuteronomy 34:1-4 Psalm 8 2 Corinthians 13:11-13 Matthew 28:16-20

At the other end of my ministry, when I was a curate at a parish in Portland, Oregon, I preached a sermon entitled, “Famous Last Words.” I don’t remember what the scriptural text was that day, but it might well have been Jesus telling his flock that he was leaving, but not to worry, because the Holy Spirit would be sent to accompany them on their journey ahead and lead them into all truth. What I do remember is a parishioner telling me afterwards that she would always remember her 18-year-old son’s last words to her as he headed out for a Friday evening with his friends: “See you later, Mom!” That night, he was killed in a motorcycle accident.

We remember last words. — Jesus on the cross: “Father, forgive them for they don’t know what they are doing.” Bob Hope’s last words were: “Surprise me.” Eric Garner was choked to death by a New York City police officer in 2014 as he said, “I can’t breathe.” And on May 25th this year, George Floyd, another black man, said, as the life was being pressed out of him by another police officer: “Don’t kill me.”

We have seen in recent days how last words can take on a power of their own, concentrating the attention of people around the world, bringing people out of their pandemic sheltering and into crowded public places to protest the abuses of power, especially against people of colour. If there is any good news coming out of the horrific scenes we have been seeing, it is that some bad actors, accustomed to behaving without accountability, are being charged with crimes. The ubiquity of cell-phone cameras means that it is no longer a matter of he said-they said. We may be watching the first glimmer of meaningful reform. Time will tell.

Today is Trinity Sunday, Holy Trinity’s feast of title, and were this a regular Trinity Sunday, the first reading would likely have been the appointed Hebrew Scripture reading of the story of Creation at the beginning of Genesis. But since it is also my last Sunday with you, I asked for a passage from the other end of the Torah, where Moses—after journeying with the Israelites out of Egypt, through the Red Sea, and into the wilderness for forty years—is shown the promised land, but told he will not live to join them in the land of milk and honey. We at Holy Trinity have been on a journey together for twelve years, and a few years ago, when I called for a strategic planning process for Holy Trinity’s future, we engaged in an environmental scan of what was happening around us, we consulted with members of the parish, with those who frequent our spaces, and with some of our neighbours, as well as researching what downtown churches in other North American cities have done to imaginatively adapt to a changing world. We settled on a model to work towards, and began to implement it incrementally with hiring for new positions. A year ago we called our first Community Director, and our commitment to the transition to the new model was incarnated in the calling of Zachary Grant. None of us knew how fortuitous the timing was, but as we look back on the last few month of living under pandemic, it is providential that we had in place the leadership, the staffing, and the volunteers to do the amazing work that has happened on the front lines on Trinity Square. Unlike Moses, I have been privileged to see a bit of the vision in store for Holy Trinity before my retirement, and it is very encouraging.

As I have been sorting and cleaning out files in my office, I came across the final report to the parish from the selection committee that resulted in my being called to Holy Trinity. They described their disappointment at being prevented by the Area Bishop’s office from considering any priest who was in a same-sex partnership. For years the parish had fought fiercely for acceptance of sexual minorities by the Anglican Church, and Canada had removed barriers to marriage several years before. As I held the report in my hands, the irony was inescapable. Our own Area Bishop now is married to another man, and they have two children together. Those decades of passionate advocacy did finally yield results.

I also came across the file from my Induction, and as I looked through the bulletin for that service in November, 2008, I noticed the words that I have heard at the many inductions I have attended since then around the diocese. Both the new priest and the members of the congregation commit themselves to one another, “bringing our strengths and weaknesses, our hopes and concerns, our gifts and talents bestowed on us by God’s Grace, and [we] endeavour with the help of God, to share with [one another] in the ministry of this parish, in the name of Christ, with the empowering of the Holy Spirit.” There is that trinitarian language embedded in the DNA of our ministry covenant. We acknowledge that there is not only one way of knowing God, experiencing God, understanding God. But the very essence is relational—within the Godhead and with Creation and with one another.

In the Season of Lent in Year B of the three-year lectionary, the readings from the Hebrew Scriptures focus on the biblical covenants in the Torah: with Noah and his family, with Abraham and Sarah, and with Moses and the Israeilites. Two years ago, I invited Rabbi Tina Grimberg to preach on the Third Sunday in Lent. The Hebrew Scripture was about God giving Moses the Ten Commandments. As she elaborated on that story, reminding us that the first tablets Moses brought down from Mount Sinai were shattered when he threw them down in anger over the idolatry of the Israelites worshiping a golden calf, and had to ascend the mountain another time to receive a replacement set. Rabbi Grimberg noted that the Bible does not say what happened to the broken pieces of the first tablets, but the Talmud explains that the people gathered them up and placed them in the Ark of the Covenant, along with the new tablets, so the broken pieces traveled with them wherever they went. I found that image a powerful one that has resonated with me ever since. Wherever we go, as individuals and as a community, we carry with us our brokenness and our wholeness, our failures, our successes, as well as our hopes and promises.

When people ask me what I am going to do in retirement, I tell them that I am planning to spend a year of living Jewishly. One of Bishop John Spong’s first books was called This Hebrew Lord. It is about how much of the Jesus we know in the New Testament is shaped by the life he lived as a faithful Jew. Setting aside one year after 35 years of parish ministry to focus on something that is at once familiar, but also distinctly different has a certain appeal to me. I can connect to a synagogue, experience the rhythm of the Jewish religious festivals, and work on my Hebrew. I will ask forgiveness for not keeping kosher.

I would like to end with a story I have told before. It is more like a parable, and like Jesus’ parables, there are multiple versions.

There once was a rice farmer who lived a very simple life. He had enough to feed and provide for his family, and he had a horse to carry his rice to market. One day, during a thunder storm, the horse panicked and ran off. The farmer’s neighbours came by to offer their condolences on the bad news. The farmer replied, “Bad news, good news, who knows?” A few days later, the horse returned, and brought with it a herd of wild horses. “What good news,” the villagers told him. “Good news, bad news, who knows?” said the farmer.

The farmer’s son decided to tame one of the wild horses, but it threw him off, and the boy broke his leg. “How terrible! What bad news,” everyone said. But the farmer responded, “Bad news, good news, who knows?” The following week one of the emperor’s generals came through the village with his entourage, conscripting for the army. All the young men of the village were drafted, except the son with the broken leg. “How fortunate for you,” the villagers said to the farmer. “What good news!” By now, you know what the farmer said: “Good news, bad news, who knows?”

As we have been living through pandemic times, this story keeps coming back to me. In part, because our worship life lurched so abruptly into something so foreign to what we are used to on Sunday morning. We all miss being able to stand with one another in a circle and sing together and pass the bread and wine to each other. We miss being able to chat with our friends over soup at lunch or welcome visitors who are with us for the first time.

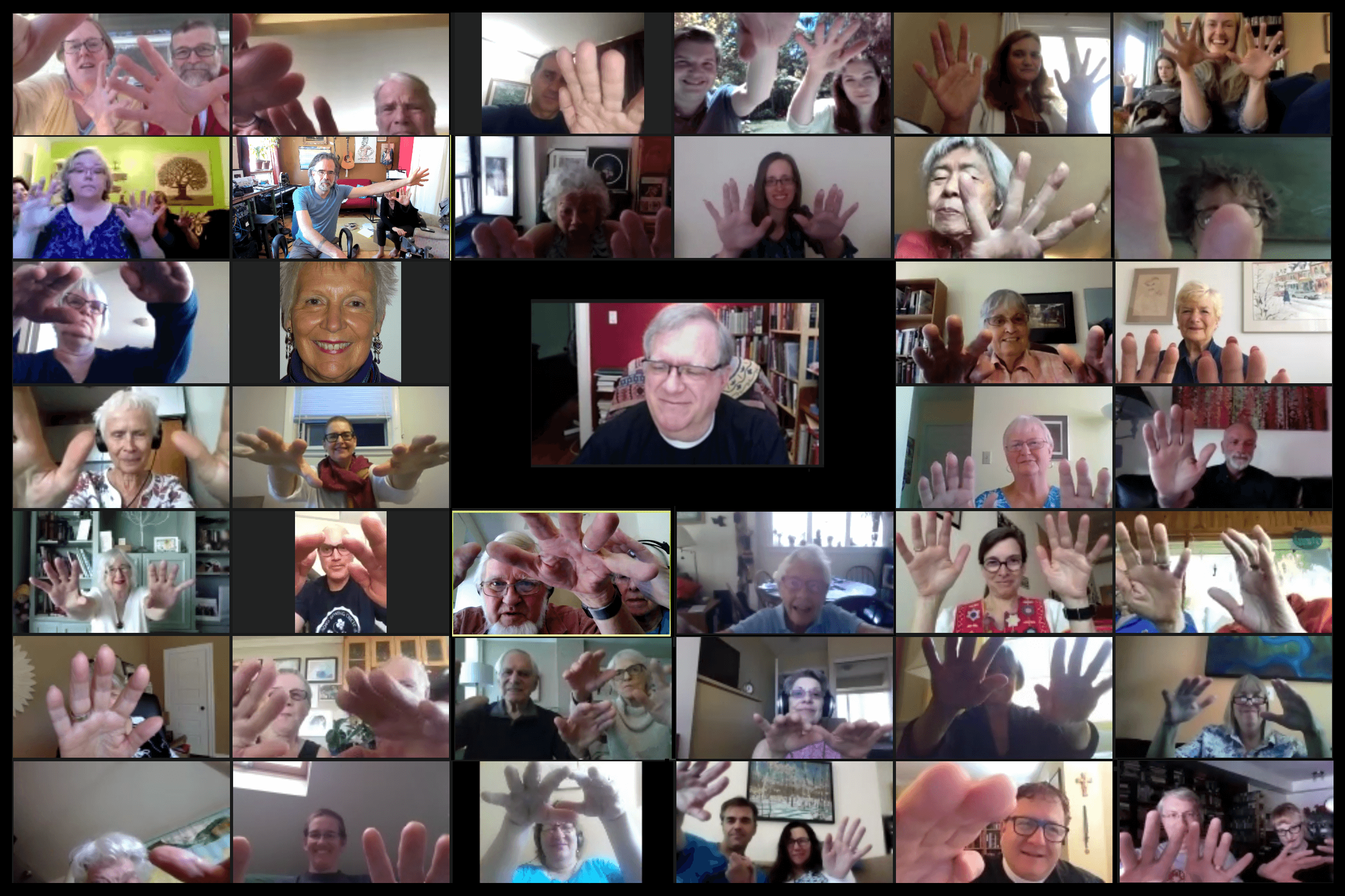

On the other hand, being able to worship by way of Zoom, means we can see and chat with people who do not live in Toronto, but who have been part of the Holy Trinity community at some time in the past, or people who have been curious to see what we are all about. So one of the conversations that will need to happen at some point is how do we keep some of the connectedness we are experiencing as a fringe benefit of the pandemic once the COVID-19 crisis has passed.

Many would say that every crisis includes both danger and opportunity. To only avoid danger, but not take advantage of the opportunities a crisis presents is to foreclose unnecessarily a future that could be creative and life-giving.

I look forward to hearing about the ventures and adventures of the Holy Trinity community, even though I will be part of the diaspora community, and living on the other side of the continent. I would like to leave you with my favorite quote by that martyr of peace and diplomacy, Dag Hammarskjöld: “For all that has been—THANKS; for all that will be—YES!”